Javier Milei and the resurgence of Mises: the Austro-libertarian praxis in Argentina

How Milei has brought the ideas of the Austrian School of thought into political action

Since Javier Milei assumed the presidency of Argentina, an unprecedented phenomenon in contemporary history has become increasingly visible: a head of state who, without ambiguity, declares himself an intellectual disciple of Ludwig von Mises, a devoted reader of Murray Rothbard, and a determined promoter of the Austrian School of Economics.What for decades was considered a heterodox or marginal current in academic and political circles is now being applied as a roadmap for the economic and institutional redesign of a nation that has, for decades, been an emblem of interventionist decline.

Walter Block, one of the leading living exponents of Austro-libertarianism, stated that if Mises were alive, he would probably feel proud of the path Milei is forging. With good reason. Not only because of the explicit vindication that Milei makes of Misesian thought, but also because of the methodological, theoretical, and ethical coherence with which he has decided to confront Argentina's economic disaster.

Misesian praxis in politics: from theory to state action

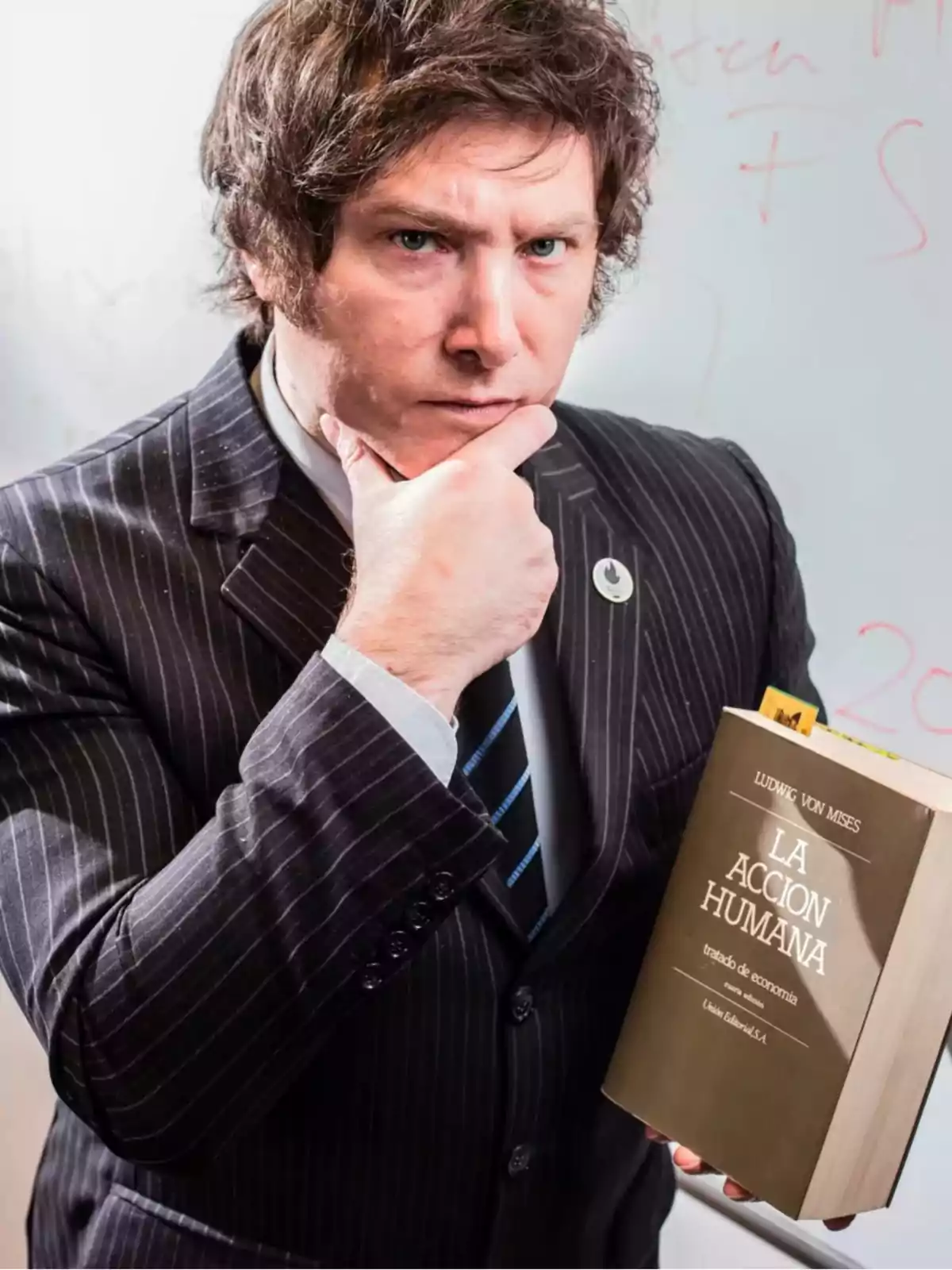

Ludwig von Mises understood that interventionism was an intermediate and self-destructive phase between the free market and socialism. Through works such as Human Action and Bureaucracy, he explained how inflation, price controls, and central planning distort the price system and destroy productive incentives. Javier Milei, aware of this diagnosis, has implemented several measures that can be read as a direct translation of Misesian analysis: the drastic reduction of public spending, the elimination of unnecessary regulations, and the explicit exposure of the monetary causes of inflation.

One of the most representative elements of this praxis has been the closing of the primary fiscal deficit in record time, as well as the implementation of structural reforms aimed at liberalizing the economy. This includes deregulation of trade, reduction of the entrepreneurial state, and opening to international capital, all under the narrative of individual sovereignty, private property, and competition as a civilizational pillar.

Milei has also vindicated the role of the subjective theory of value, central to the Austrian School, by rejecting Marxism and its objectivist conception of labor-value. His message, repeated like a mantra, "the state is not the solution, it's the problem," is nothing more than a modern reformulation of Misesian and Hayekian laissez-faire.

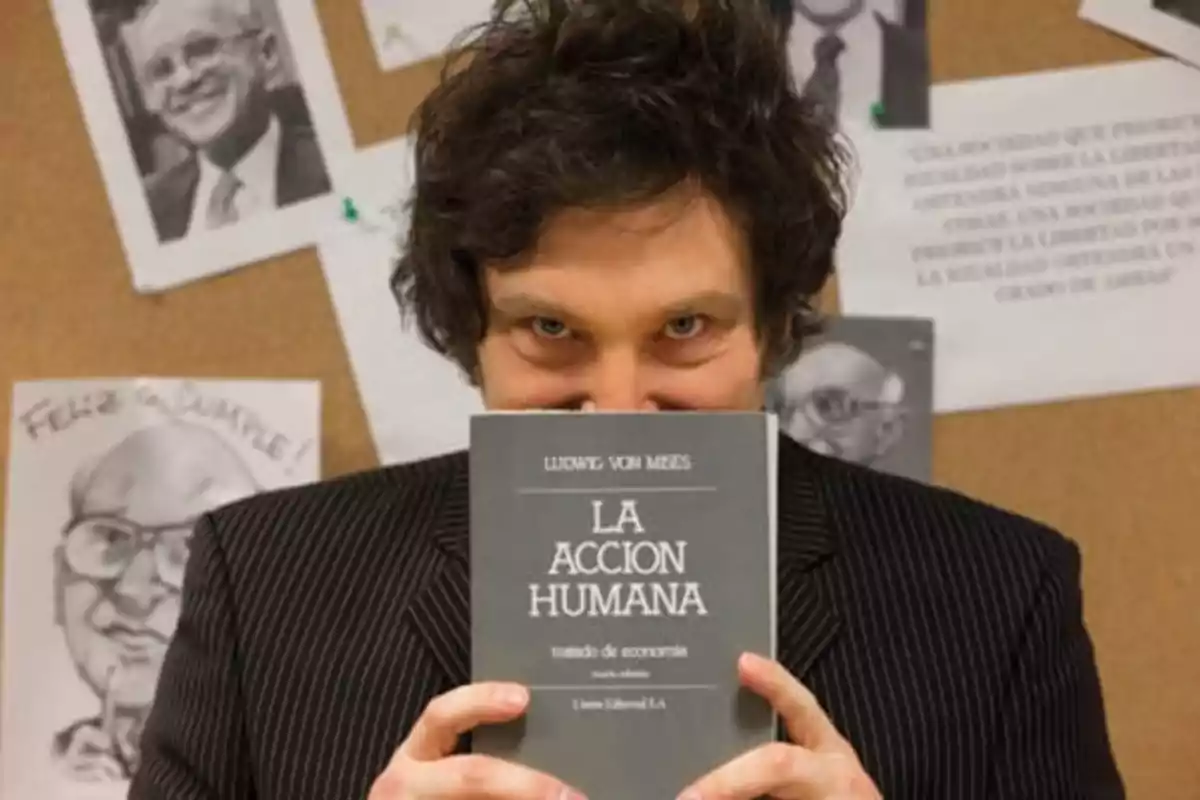

Milei before the presidency: outreach, philosophy, and the cultural battle

Long before holding public office, Javier Milei was already waging a cultural, ideological, and philosophical war. His participation in media, conferences, and debates not only consisted of economic analysis but also of the passionate defense of philosophical principles linked to classical liberalism, minarchism, and even Rothbardian anarcho-capitalism. In interviews and presentations, Milei would quote from memory authors such as Carl Menger, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, Mises, Hayek, and Rothbard, directly challenging the statism rooted in Argentina's political culture.

In this process, Milei played an almost missionary role, rescuing Austro-libertarian thought from oblivion in the Spanish-speaking world, inspiring young people, economists, activists, and academics who began to rediscover the ideas of economic freedom, individual responsibility, and natural law. His emphasis on the morality of the market, the illegitimacy of state theft via inflation or taxes, and the defense of the individual against the coercion of Leviathan, directly links him to Lysander Spooner and Murray Rothbard, for whom freedom was not only useful, but just in itself.

Milei thus became a philosophical figure, not merely a technical one. His discourse was imbued with a radical critique of statism from both ethics and epistemology, "socialism is impossible," he would repeat, paraphrasing Mises, not only for economic reasons but because it violates the very logic of human action and voluntary cooperation.

Convergence with Jesús Huerta de Soto and the advance toward a free society

One of the most interesting parallels in Javier Milei's thought occurs with Spanish economist Jesús Huerta de Soto. Both share a frontal critique of central banking, the fractional reserve system, and the fiduciary manipulation of money. Milei has stated on multiple occasions that the Argentine Central Bank must be eliminated for being a morally corrosive and technically destructive institution, a stance aligned precisely with Huerta de Soto's thesis in Money, Bank Credit, and Economic Cycles.

Likewise, Huerta de Soto has insisted that true institutional reform must be based on principles of natural law, private property, and voluntary contracts. Milei, in his own way, has brought this vision to the political arena by promoting institutional reforms that limit state power, strengthen individual rights, and foster entrepreneurial action as the basis of progress.

This convergence is not accidental. Milei and Huerta de Soto draw from the same tradition, a tradition rooted in late scholasticism, in the moral philosophy of natural law, and which has been revived by modern authors such as Hans-Hermann Hoppe and Peter Boettke. Both recognize that economics can't be separated from ethics or epistemology, and that without a clear moral foundation, all economic policy tends toward totalitarianism or chaos.

The case of Milei therefore represents a historical turning point. Not only because, for the first time, a president is implementing measures directly inspired by the Austrian School, but because he does so with a philosophical clarity rarely seen in contemporary politics. He has achieved what many thought impossible: bringing abstract ideas, often confined to seminars or libraries, into public debate and institutional action, sowing a realistic hope for structural transformation.

Ultimately, Milei is not just an economic reformer; he is a liberal Renaissance man amid the Keynesian twilight. In this battle, he has not only revived Mises, Hayek, Rothbard, or Huerta de Soto, but has shown that ideas, when they are solid and true, can and must change the world.

More posts: