The Cultural Battle in Diplomacy

Redefine Argentine diplomacy with freedom, efficiency, and a determined cultural battle against statism

We are living in times of inflection. Traditional diplomatic institutions, shaped by centuries of history, customs, traditions, and bureaucratic hierarchies, are facing a crisis of meaning. Diplomacy, which was once an instrument of conciliation between states and a symbol of state refinement, has in many cases become an obsolete, bureaucratic, and parasitic tool.

In Argentina, in particular, it has become a bastion of corporate privileges, reflecting a hypertrophied state structure that serves statism, welfare dependency, and the myth of the welfare state. This document proposes a redefinition of Argentine diplomacy based on the principles of freedom, efficiency, and cultural struggle, inspired by the ideas of Frédéric Bastiat, Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek, Israel Kirzner, and the leadership of President Javier Milei, integrating a historical and critical perspective from Austrian economics, along with an analysis of the limitations of the UN.

History and Critique of Traditional Diplomacy

Diplomacy has deep roots in human history. Since 3000 BC, civilizations such as Mesopotamia and Egypt laid the foundations of this practice. In Mesopotamia, city-states used messengers to negotiate treaties, while in Egypt the pharaohs established agreements with neighboring kingdoms, marking the origins of formal diplomacy. In fifth-century BC Ancient Greece, the poleis developed a structured diplomacy with temporary embassies to forge alliances. The Roman Empire advanced toward more modern practices by establishing permanent representatives for international affairs.

During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, cities such as Florence and Venice institutionalized permanent embassies to protect commercial and political interests, setting precedents for modern diplomacy. The Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 consolidated state sovereignty, while the Congress of Vienna (1814-1815) reorganized the European political order after the Napoleonic wars. In the twentieth century, the creation of the League of Nations in 1919 and the UN in 1945 sought to formalize international cooperation, although often at the cost of increasing bureaucratization.

Traditional diplomacy, often presented as a professional and meritocratic body, has become a closed aristocracy, disconnected from national interests. Shielded by obsolete regulations, it keeps unsustainable privileges: salaries in dollars, state housing, drivers, domestic services, tax exemptions, and special pensions. These costs, which reach millions of dollars annually, are unjustifiable in light of taxpayers' needs. For example, the maintenance of embassies, such as those of the United States, involves an approximate budget of 55 billion dollars per year, while the UN had an operating budget of 3 billion dollars in the 2020-2021 biennium, not including additional funds.

From the perspective of Austrian economics, inspired by Mises and Hayek, this centralization and bureaucratization introduce rigidities and economic costs that undermine individual freedom. Diplomatic decisions, guided by political criteria instead of citizens' preferences, generate inefficient policies that are detached from market dynamics. Furthermore, the diplomatic failures of recent decades, such as the inability to prevent conflicts in the Middle East or the Balkans, highlight the limitations of these centralized structures.

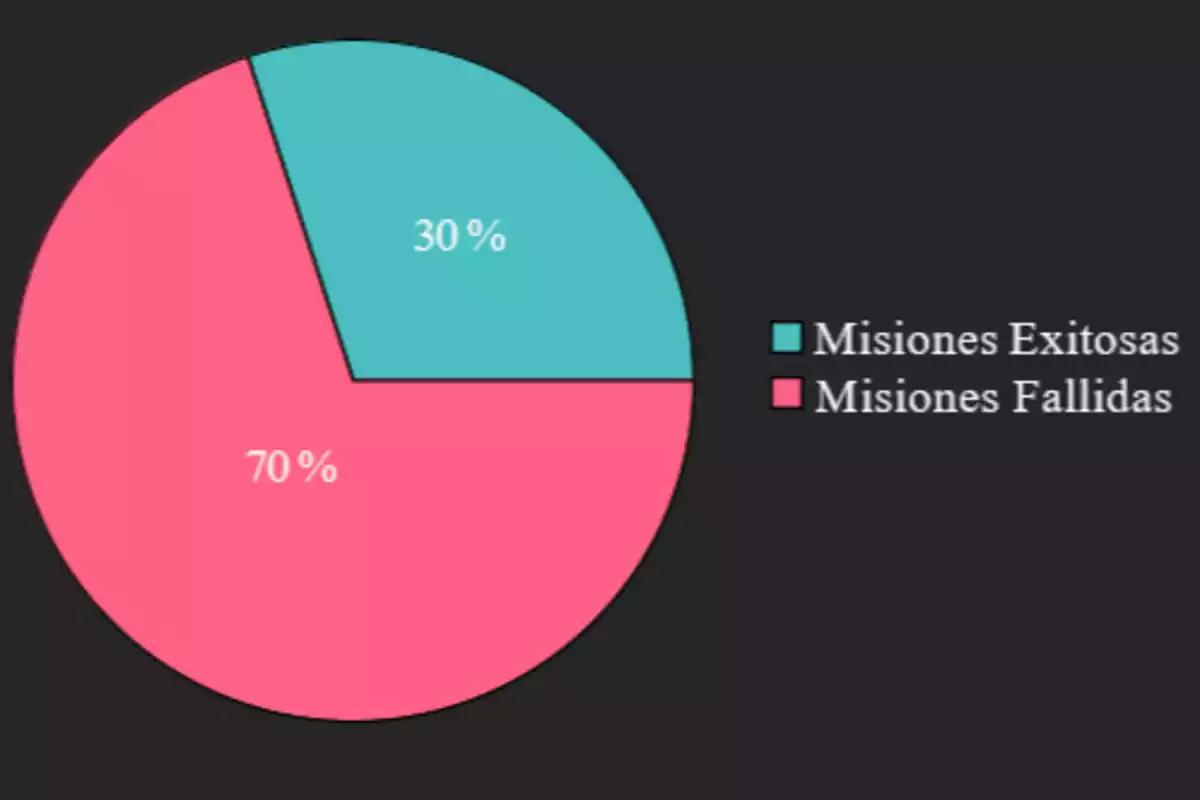

Figure 1: Successes vs. Failures in UN Peacekeeping Missions (1948-2023). Own elaboration based on SIPRI and Human Rights Watch reports.

Toward a Libertarian Diplomacy

Diplomacy aligned with libertarian principles and Austrian economics must prioritize efficiency, specialization, and fiscal responsibility. Commercial functions and export promotion can be delegated to private or semi-private entities, such as binational chambers of commerce or the Argentine Investment and International Trade Agency (AAICI), which operate with business logic. Maintaining a diplomatic corps that duplicates these functions runs counter to Mises's principle of allocating resources to citizens, not the state. Likewise, Hayek's notion of spontaneous order and Kirzner's entrepreneurial discovery support a mixed model in which the state is limited to essential functions—political representation, treaties, and emergency consular protection—and delegates the rest to the private sector.

In the digital age, consulates can operate in networks, manage procedures online, and offer remote services, eliminating the need for costly physical structures. Current technologies, such as email, videoconferencing, and social networks, enable more direct and personalized diplomacy, but traditional bureaucratic structures have hindered their full utilization. Modern diplomacy must be agile, decentralized, and responsive to market demands, reducing the economic burden represented by embassies and consulates.

Diplomacy as a Cultural Battle

The transformation of diplomacy goes beyond administrative reforms and is situated in the realm of ideas, as President Javier Milei has emphasized. Diplomacy is not a neutral technical exercise, but a key front in the cultural battle against globalist collectivism. Frédéric Bastiat, in his work The Law (1850), warned of the dangers of state interventionism, which diverts resources and individual freedoms toward imposed collective ends. In the diplomatic sphere, this critique is particularly relevant: international institutions such as the UN, OAS, or World Bank have been co-opted by agendas that, under the pretext of global cooperation, promote policies that restrict individual freedom and distort market dynamics.

Bastiat, with his concept of what is seen and what is not seen, would argue that the visible costs of globalist diplomacy—multi-billion-dollar budgets for embassies and international organizations—are only a fraction of the problem. What is not seen are the lost opportunities: the resources that citizens could have used to innovate, undertake, and prosper, but which are confiscated to finance bureaucratic structures that perpetuate statism. For example, the UN, with an operating budget of 3 billion dollars in the 2020-2021 biennium, and global embassies, such as those of the United States with 55 billion dollars annually, represent a massive extraction of wealth that Bastiat would describe as legal plunder. This plunder not only impoverishes taxpayers, but also legitimizes collectivist narratives that prioritize global agendas over individual freedoms.

In this context, libertarian diplomacy must be an active instrument to counter these narratives. For decades, the left has dominated international organizations, shaping language and policies to promote statism, from radical feminism to interventionist environmentalism. As Bastiat pointed out, the state tends to become the great fiction through which everyone tries to live at the expense of everyone else. Internationally, this is manifested in resolutions that impose coercive regulations, global taxes, and controls that stifle economic freedom. Diplomacy inspired by Bastiat, Mises, Hayek, and Kirzner must reject these impositions, instead promoting individual freedom, the market economy, and spontaneous order in forums such as the G20, regional summits, and missions to the United Nations.

Diplomats must be ideologically prepared to defend these principles, not just to administer inherited structures. Embassies and consulates must not fund NGOs that promote coercive policies or support resolutions that expand state control. As Milei stated, without a cultural battle, economic and administrative advances will not be sustainable. From Bastiat's perspective, this battle involves exposing the unseen consequences of globalism: the loss of individual sovereignty, the sacrifice of private initiative, and the perpetuation of a system that, under the guise of cooperation, undermines the foundations of a free society. Libertarian diplomacy must project a national project that prioritizes freedom, consistent with Bastiat's ideas on respect for property and non-intervention, and with the visions of Mises, Hayek, and Kirzner on market efficiency and spontaneous order.

A New Diplomatic Era

To materialize this vision, it is urgent to reform the Argentine Foreign Service. This involves reviewing the Foreign Service Law, eliminating privileges, closing irrelevant posts, digitizing functions, and training diplomats with firm convictions. Diplomacy is not just protocol; it is ideology, soft power, and cultural battle in the service of a national project. In Argentina, that project is freedom, with a reduced state, free markets, and sovereign citizens.

Twenty-first-century diplomacy must choose between remaining an obsolete vestige or transforming into a cutting-edge tool. Inspired by the ideas of Bastiat, Mises, Hayek, Kirzner, and Milei's leadership, Argentina can lead a diplomacy that not only represents the state, but defends freedom in every embassy, consulate, and international statement. As Mises said, progress always came from those who challenged established forms. The time has come for diplomacy that not only manages, but transforms.

By Alejandro Nimo and Julio Goldenstein, presidential advisor.

More posts: