Day of the Cockade: how the sky blue and white national symbol was born

Learn about the history and debates surrounding the origin of the cockade and its light blue and white colors

The origin of the national cockade is closely related to that of the patriotic colors: sky blue and white. In reality, it is not known for certain when this bicolor combination began to be used to represent us.

There are many hypotheses that refer to the origin of the patriotic colors that identify us today. Some claim that these colors were first adopted after the First English Invasion by the Regiment of Patricians, in the bicolor feather plume that, it is believed, the soldiers wore on their hats; when this force was created by Santiago de Liniers, back in September 1806.

Another precedent dates back to mid-July of that year, when Juan Martín de Pueyrredón settled in the town of Luján. There he recruited a force of between six hundred and fifty and eight hundred countrymen, laborers, and armed blandengues, with the intention of reconquering Buenos Aires from the English invaders.

Faced with the great disparity of clothing and the lack of uniforms for all these volunteers, Father Vicente Montes Carballo, who attended the Santuario de Luján, distributed to them, to use as insignia, sky blue and white ribbons, approximately thirty-eight centimeters long; which were called: "measures of the Virgin," with the colors of the mantle and tunic of Our Lady of Luján and an extension equivalent to the height of the image.

Others have recorded that on May 18, 1810, when it became known about the proclamation of Viceroy Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros, which released the fall of all Spain into the hands of Napoleon, the patriots, who were gathered at the house of Nicolás Rodríguez Peña, decided to urgently summon the undisputed military leader of the city, who was Cornelio Saavedra, to convince him to support the revolutionary movement they planned to initiate. Don Cornelio was not in the Capital at that time; he was at his weekend estate in San Isidro. So, the patriots asked his great friend, Juan José Viamonte, to send for him.

This is how Saavedra recalls that day: "I was in the town of San Isidro that day. D. Juan José Viamonte, Sergeant Major of my corps, wrote to me saying that it was necessary for me to return to the city without delay, because there were important developments. I did so. When I presented myself at the house, I found there a portion of officers and other countrymen."

Back in Buenos Aires, and cautious and distrustful as was his character, Saavedra did not immediately go to Rodríguez Peña's, but to his friend Viamonte's house, where he surely felt more comfortable, to carefully consider his steps, due to the seriousness of the events that had occurred.

As time passed and Don Cornelio did not appear, the patience of the patriots at Rodríguez Peña's house began to run out. It was at that moment that the lady of the house intervened, Casilda Igarzábal de Rodríguez Peña, who, accompanied by other patrician ladies: Ana Estefanía Dominga Riglos de Irigoyen, Melchora Sarratea, and perhaps the wives of Juan José Castelli and Pedro Agrelo, decided to take the bull by the horns and do what the men did not dare: go to meet the indecisive leader of the Patricians and convince him to support the nascent May Revolution.

Thus, these ladies, who carried with them sky blue ribbons edged with white (tradition says) arrived at Juan José Viamonte's, and once they entered the house, they confronted the surprised Cornelio Saavedra, to demand that he make a decision. It seems that seeing the women so determined was what led the Potosino to favor the May Revolution instantly. They say that Doña Casilda finished persuading him when she told him to be bold, for "there is no need to hesitate."

Another precedent regarding the use of patriotic colors is mentioned by Ignacio Núñez, in his "Historical News of the Argentine Republic." Núñez recounts that the soldiers of the Northern Army, who departed on July 9, 1810, under the orders of Antonio Ortiz de Ocampo, to confront Santiago de Liniers, "wore the Spanish yellow and red cockade on their hats, and on the muzzles of their rifles, white and sky blue ribbons." Many have questioned this precedent, and some believe it is possible that soldiers marching to the North at some point wore sky blue and white ribbons; but it is very likely that these events occurred years later when these colors were already established among us.

However, the oldest origin of the sky blue and white colors in Argentine symbolism dates back to the colonial coat of arms of the city of Buenos Aires, created in 1649, formed by an oval divided into two halves: the upper sky blue (for the sky) and the lower, white (or silver, for the Río de la Plata).

Bartolomé Mitre, more than fifty years after the events, recounts that on May 22, 1810, Domingo French "entered one of the shops of La Recoba and took several pieces of white and sky blue ribbons, colors popularized by the Patricians in their uniforms since the English Invasions, and which the people had adopted as a party emblem in the previous days. Immediately posting pickets on the avenues of the Plaza, he armed them with scissors and white and sky blue ribbons, with orders not to let anyone in but the patriots, and to make them wear the emblem. Beruti was the first to hoist the patriotic colors on his hat that would soon triumphantly traverse all of South America. Instantly, the entire popular gathering was seen with sky blue and white ribbons hanging from their chests or hats. Such was the origin of the colors of the Argentine flag, whose memory has been saved by oral tradition."

This confusion surely originated from the version given by a contemporary witness of the events, such as Cornelio Saavedra, who in his memoirs, written more than fifteen years after the events, and included this fragment in Mitre's work, noted that on May 22, 1810: "the Plaza de la Victoria was full of people, who were already adorned with the emblem on their hats, of a blue ribbon and others white."

It is true that the Creole picketers, called "chisperos," took over the Plaza and only allowed their supporters to enter the Open Cabildo. However, there are no reliable contemporary records to corroborate Mitre's version, obtained from some surviving witnesses and mainly from Saavedra, that the distribution of blue or sky blue and white ribbons took place in May 1810.

It is very likely that the latter confused and mixed up the events after so much time. It is true that French organized pickets and distributed ribbons in 1810; but they were not sky blue and white.

It is also true that French distributed sky blue and white ribbons; but he did so only a year later, and not during the May Week of 1810.

Returning to our curiosities, what color were the ribbons actually distributed by the "chisperos" of French and Beruti in May 1810?

Juan Manuel Beruti (brother of the "chispero" Antonio Luis Beruti) refers in his "Curious Memories" that the Creoles wore white ribbons in the buttonholes of their jackets, "a sign of the union that reigned, and on the hat a red cockade and an olive branch as a plume". White was the traditional color of the Bourbons, both in France and in Spain "and signified the union between American and European Spaniards"; as a manifesto to the equality of treatment and access to Government that the Americans demanded during the Revolution, without breaking with the King.

The American sailor Nathan Cook was present in Buenos Aires during the May days, and he was the supercargo of the merchant brig "Venus." He, upon returning to his homeland, in an article published on April 7, 1812, in the Massachusetts newspaper called Salem Gazette, recalled that "On Monday the 21st, the alarm began at dawn; the patriots' hats were adorned with the portrait of Fernando VII, on which, and in the buttonhole of the jacket, they wore a white ribbon signifying, as he says, union among themselves and fidelity to Fernando VII in case the throne is restored."

In conclusion, all contemporary testimonies of the time indicate that the ribbons distributed by the patriots led by Domingo French and Antonio Luis Berutti were white. These ribbons adorned portraits of Fernando VII, which the patriots carried during the May days, in order to disprove the accusation made by the royalists that they intended independence from the Metropolis.

Having made these prior clarifications, let us now return to our account regarding the documented origin of the First National Cockade, which brings us very interesting data. In 1810 Mendoza was part of the Province of Córdoba del Tucumán. It was headed by a Lieutenant Governor, who reported to Córdoba, the head city of the Intendancy.

In August, José de Moldes arrived in Mendoza; a brave, arrogant, and proud man from Salta, who studied and fought in Spain, and embraced the revolutionary cause from its inception. The First Junta appointed him Lieutenant Governor of that jurisdiction.

Shortly after arriving, and in the absence of militias he found in Mendoza, Moldes created two companies of "halberdiers." The halberdiers were soldiers armed with "halberds." The halberd was a Renaissance weapon, a mix of spear and axe.

On the last day of the year 1810, Moldes wrote to the Junta an official letter, where he communicated: "To these two companies I have given a national cockade, which I have formed with reference to the south, sky blue, and the tips white for the spots that this sky we already see cleared has... The meeting of the provinces seems to give room to consider the time for the use of a national cockade and a proper rank for it, especially when all nations have it and it is necessary for our countrymen to raise their heads, which they still carry low. I would like it to be of your excellency's approval and in the meantime, your excellency's order comes, I have it placed on my hat. God save your excellency for many years. Mendoza December 31, 1810. José de Moldes."

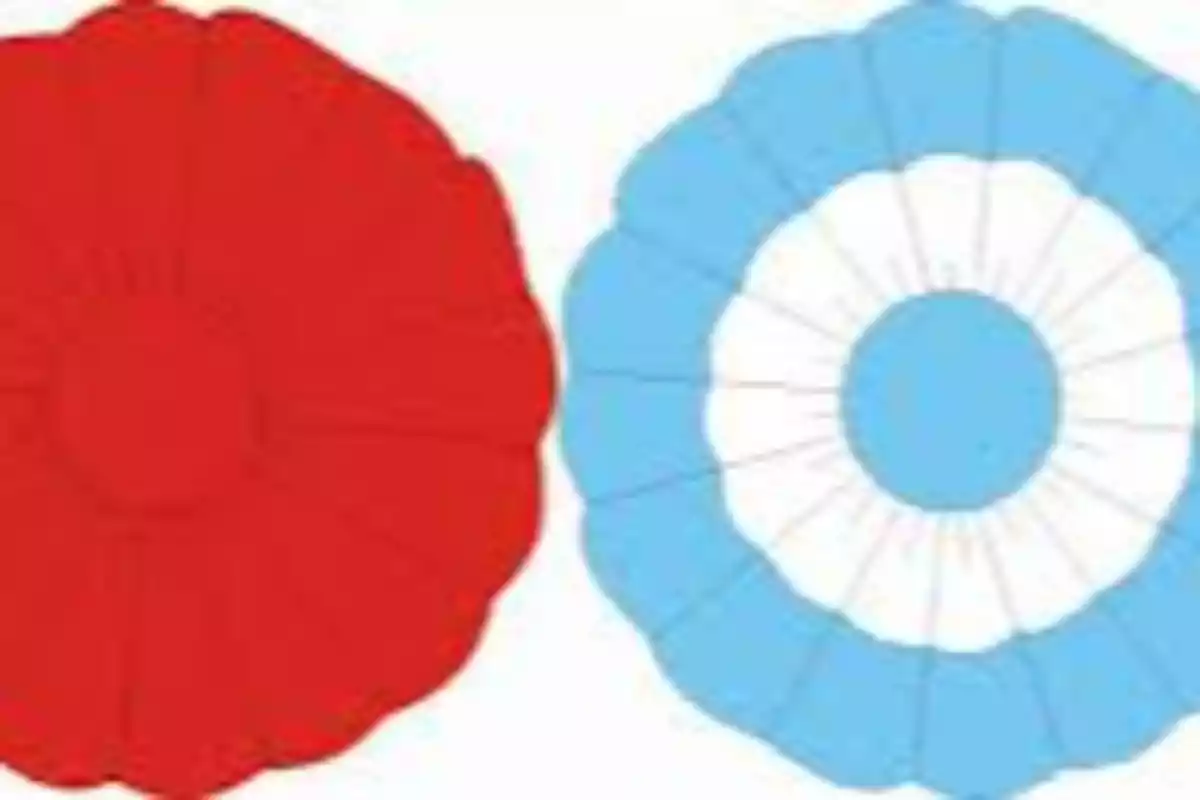

This is the first concrete documentary reference to a national cockade, with the patriotic colors, created by a man from Salta, in Mendoza, which was worn by the Mendocino Halberdiers. Moldes explains that from the southern sky he took the main color of his "cockade": sky blue, and from the clouds that are dissipating, he obtained the secondary color: white. Moldes's cockade was round, with a thick sky blue border and a small white center.

This note was never answered by the Junta Grande, dominated by Saavedristas and provincials, who had already solved to relieve Moldes; who sympathized with "Morenism," from his position in Mendoza, to assign him to the Banda Oriental. Twelve days after sending this communication, Moldes departed for his new destination, without knowing that the Government never solved anything about his cockade.

Our first National Symbol had to wait then, a little over a year to be officially introduced. Only on February 18, 1812, Bernardino Rivadavia ordered, in his own handwriting: "Let the National Cockade of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata be of white and sky blue color and communicate it to the Government and General Staff". Our first "official" cockade was, curiously, the reverse of Moldes's emblem: with a wide white border and a small sky blue center.

Time would do the rest, and it would combine, oddly, Moldes's first "informal" cockade with Rivadavia's first "official" cockade, resulting in the emblem that we Argentines wear today: sky blue borders and center; separated by a white stripe in the middle, following our flag.

More posts: