From Solow's model, Romer's contribution, and Javier Milei's application

A technical overview of growth models and their impact on economic policies

In the mid-20th century, the analysis of economic growth experienced an essential shift with the nearly simultaneous work of Robert Solow and Trevor Swan, who developed what we now know as the neoclassical growth model. This model sought to correct the dynamic instabilities of the previous Harrod and Domar models, which were characterized by an unstable structure highly sensitive to assumptions about the capital-output relationship.

Swan's contribution, parallel to Solow's, consisted of a rigorous mathematical formulation of the balanced growth path. Swan introduced a model where the long-term growth rate is determined by exogenous technological growth and population growth, under assumptions of diminishing returns to physical capital. His Australian version of the model was less disseminated than Solow's but conceptually analogous and key to the formalization of equilibrium growth trajectories.

However, when empirically applying his model to the U.S. case, Solow discovered a surprising result: the accumulation of per capita physical capital failed to explain most of the economic growth observed in the analyzed period. The unexplained portion, later termed the "Solow residual", indicated the existence of other factors beyond capital and labor. That gap could not be ignored: the model failed to explain the most relevant drivers of real economic growth. From there, the need arose to incorporate new explanatory variables.

The emergence of human capital: Becker and Uzawa

Faced with the challenge of explaining the Solow model's residual, the Department of Economics at the University of Chicago, under the direction of George Stigler, proposed advancing the introduction of human capital as a new explanatory variable. This idea gave rise to two essential lines of research.

In the microeconomic realm, Gary Becker developed a systematic theory of human capital. Although his doctoral thesis (The Economics of Discrimination) addressed issues of discrimination in the labor market, his later work, especially the book Human Capital, laid the foundations for an economic analysis of human behavior beyond traditional markets. Becker treated human capital as a form of investment, comparable to physical capital, where education, health, experience, and job training increase an individual's productivity.

Becker introduced individual production functions that allowed modeling how private decisions on skill accumulation affect the marginal productivity of labor and, by extension, aggregate growth. His approach integrated tools from neoclassical microeconomics and intertemporal consumption theory, anticipating many of the dynamics later formalized in endogenous growth models. This analysis allowed understanding why countries with equal physical capital endowments could have divergent growth trajectories: the key was in the accumulation of human capabilities.

From the macroeconomic perspective, Hirofumi Uzawa developed a growth model that explicitly incorporated human capital as an accumulable factor in the aggregate production function. His formulation allowed for sustained growth even without exogenous technological progress, given that human capital could be increased through the allocation of time to learning and training.

The revolution of endogenous growth: Lucas and Romer

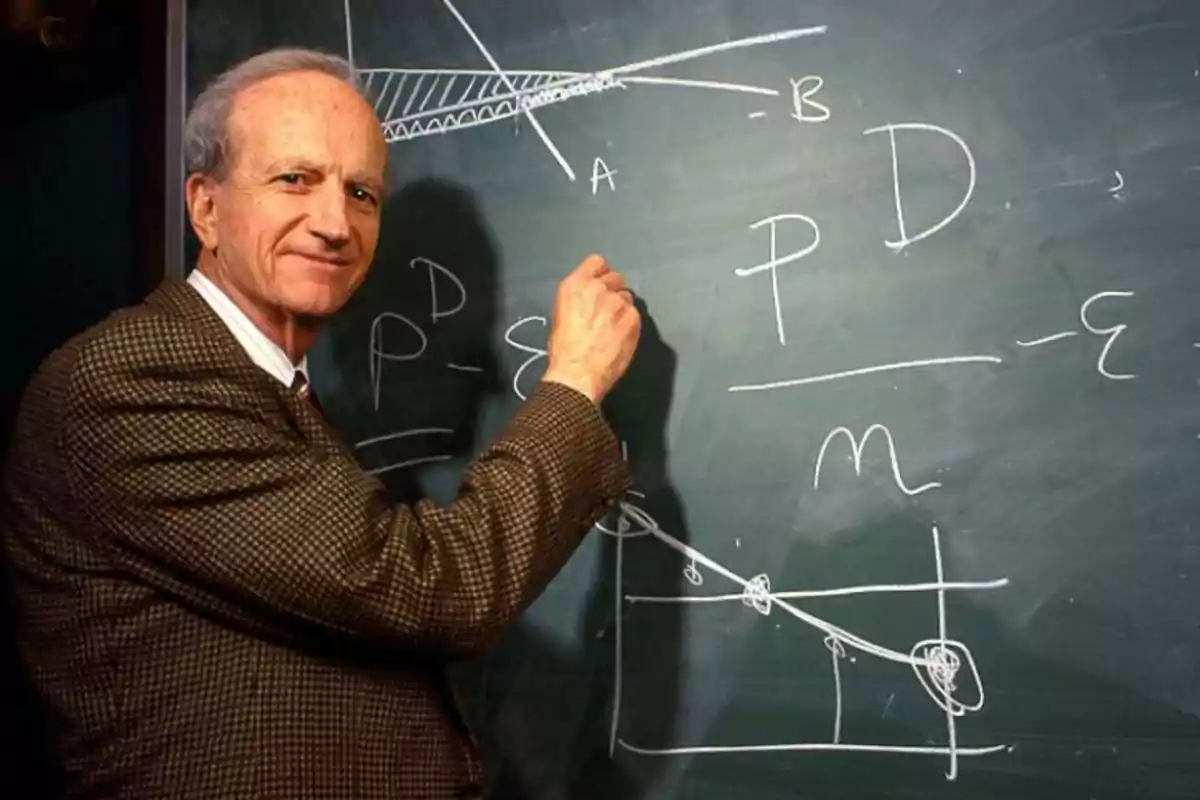

In the following decades, the Solow model continued to be the central reference, although its main limitation, the exogenous treatment of technological change, remained. This gap was finally addressed in the 1980s by Paul Romer, whose doctoral thesis at the University of Chicago, directed by Robert Lucas Jr., gave rise to the theory of endogenous growth.

Romer argued that technological knowledge is a non-rival and partially excludable good, which generates increasing returns to scale. In his model, investment in research and development by private companies generates positive externalities that sustain aggregate growth. This theory eliminated the need to assume exogenous technological progress, integrating innovation within the economic model.

Robert Lucas Jr., meanwhile, consolidated the role of human capital in growth in his 1985 Lionel Robbins Lectures, where he argued that international differences in per capita income could only be explained by persistent differences in human capital accumulation. He proposed a model with human capital externalities that allowed for sustained and autocatalytic growth, meaning that the knowledge accumulated by a few benefits the whole.

These developments spurred a renewal of the economic growth literature and opened the door to the empirical quantification of the factors involved. In 1992, Gregory Mankiw, David Romer, and David Weil expanded the Solow model by explicitly incorporating a human capital variable, showing a significant improvement in its ability to explain international growth differences. The result: the extended model with human capital offered a much more robust explanation of the observed growth.

Parallels with the Argentine case

In contrast, Argentina has oscillated for decades between import substitution models, unproductive statism, and scarce investment in quality education. The lack of an institutional environment that incentivizes investment in human capital has resulted in stagnant productivity, brain drain, and low entrepreneurial dynamism.

While countries like South Korea, Ireland, or Estonia bet on education, economic openness, and innovation, Argentina prioritized political short-termism and state clientelism.

The lesson from modern growth models is compelling: without human capital, there is no sustained growth. Economic policy must abandon the mechanistic view of physical capital accumulation and focus on designing institutions that promote learning, innovation, and individual freedom. Only then will it be possible for Argentina and other countries with similar trajectories to abandon their secular stagnation and integrate into the 21st century with full economic dynamism.

More posts: