Cabildo Abierto: how the patriots tipped the balance on May 22, 1810

Manipulated invitations, partial soldiers, and a crowded square marked the beginning of the Revolution

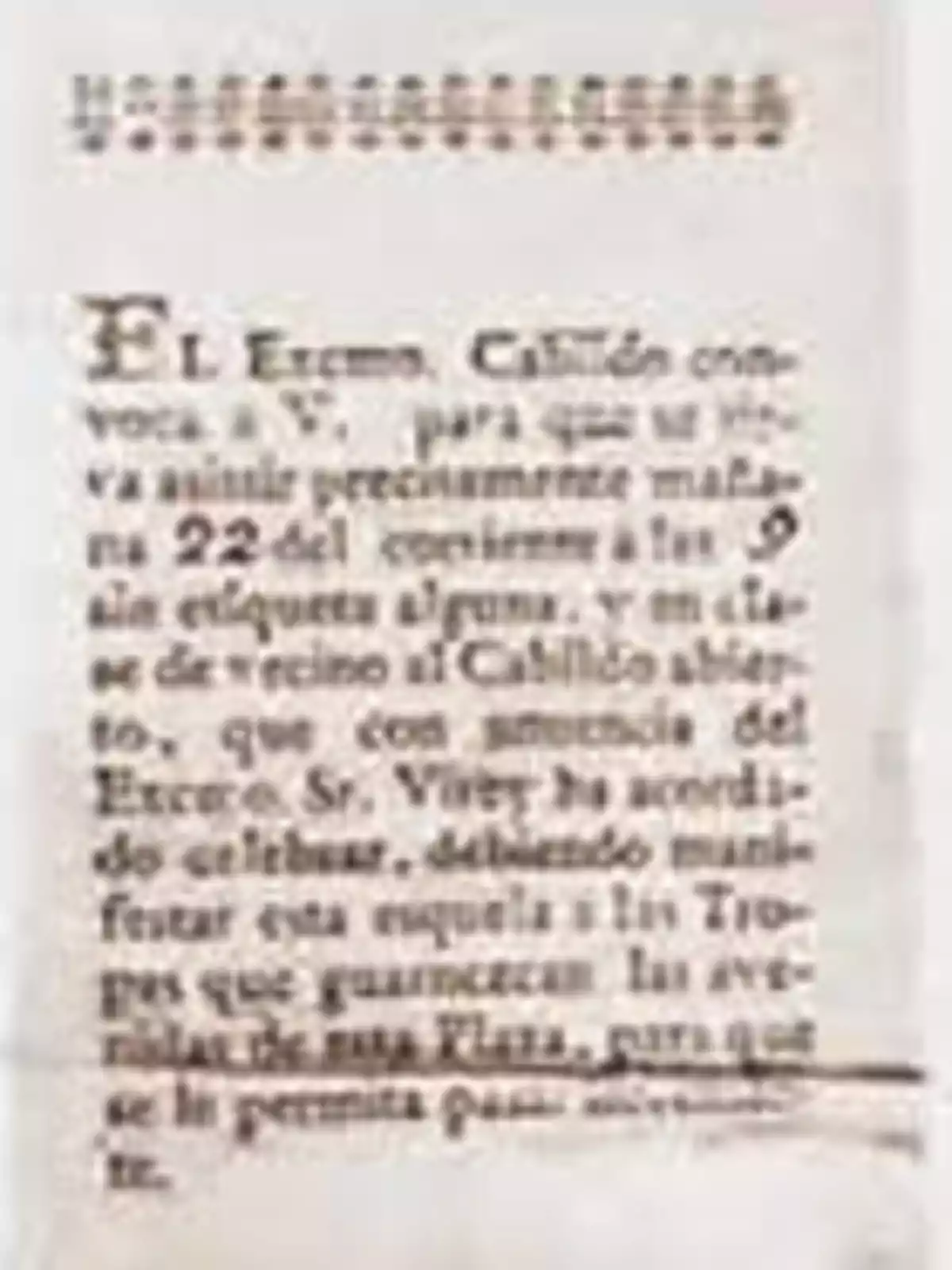

May 22 dawned cool and rainy. From early on, the Plaza de la Victoria was surrounded by soldiers' orders, arranged by the Viceroy. They were to prevent the passage of anyone not summoned to the Open Cabildo. Attendees had to show the invitation to the Creole troops stationed at the street corners; and from there they could head toward the Buenos Aires Cabildo.

To participate in an Open Cabildo, one had to be a resident with uninterrupted residence in the city, and of a certain socioeconomic level, as it was required to have a house, horse, and weapons. They were called "the main and healthiest part of the neighborhood". They could be beneficiaries of franchises and commercial permits, as well as encomenderos. They were allowed to access public positions in the Cabildo: councilors (which would be something like the current "councilors") and mayors (intendents). They were also registered in the Cabildo's records. At that time, Buenos Aires had around 45,000 inhabitants, and about 450 neighbors were in this category (approximately 1% of its population).

Irregularities in the preparation of the "Open Cabildo"

The invitations were printed at the Royal Printing House of Abandoned Children, the only one available in the city, whose concessionaire was Agustín Donado, a supporter of the May Revolution, forgotten by our history. Thus, the revolutionaries manipulated the printing and distribution of the invitations.

It is believed that 600 were printed, instead of the originally planned 450 cards. On purpose, many of them were not delivered to well-known royalist neighbors; and others were distributed, without specifying name or identification, to Creoles who should not have participated in the Open Cabildo; because they were not listed in the "register" managed by the Cabildo.

But the "tricks" didn't end there: the soldiers stationed at the access street corners to the plaza and the Cabildo did not allow several supporters of the Viceroy to enter, as soon as they were identified; even though they carried their respective invitations.

Cisneros's Version

Regarding these maneuvers, Cisneros recounts: "I had ordered that a company be stationed for this act at each street corner of the plaza, so that no one who was not among those summoned would be allowed to enter it or go up to the Capitular Houses; but the troops and officers were of the party; they did what their commanders secretly instructed them, and these instructed them what the faction ordered them: they denied access to the plaza to honorable neighbors and allowed it to those of the conspiracy; some officers had copies of the invitation cards without names and with them introduced to the Town Hall houses subjects not summoned by the Cabildo or because they knew them from the faction or because they won them over with money, so in a City of more than three thousand distinguished and named neighbors, only two hundred attended, and of these, many were shopkeepers, some artisans, others family members, and the most ignorant and without the slightest notions to discuss a matter of the greatest gravity."

Inside the venue, the Creoles were not characterized by their good manners either. Some supporters of the Viceroy would later recount that they were called "crazy" or else, "they were spat on, mocked, insulted, and whistled at."

The debate begins

With the presence of 251 "neighbors," the deliberations began at 9 in the morning. Attendees included: 56 military personnel (among them Saavedra), 18 neighborhood mayors, 4 sailors (Ruíz Huidobro), 24 clergymen (among them, Bishop Lué and priest Solá), 4 notaries (Núñez), 20 lawyers (among them: Castelli, Moreno, and Paso), 2 members of the Royal Audience (Prosecutor Villota), 4 doctors, 2 members of the Consulate (Belgrano), 13 officials, 43 merchants, and 18 who were classified as "neighbors." 43 more attendees did not specify in what capacity they intervened. Obviously, in these last two categories, the patriots who entered without being "officially" invited must have been included.

Meanwhile, the Plaza began to be taken over by enthusiastic crowds favorable to the patriots, led by Domingo French and Antonio Luis Berutti, who called themselves: "chisperos" or the "Infernal Legion," with white ribbons hanging from their hats or lapels, and portraits of Fernando VII. With these insignias, they wanted to symbolize the "UNION of American and European Spaniards," alluding to the equality in treatment and opportunities they demanded for the Creoles; who had been relegated by the peninsulars. This occupation of a supposedly "fenced" plaza revealed the degree of connivance between the approximately 600 demonstrators and the troops that were supposed to guard it. The objective was to pressure the Cabildo to obtain the dismissal of the Viceroy.

The Cabildo's Notary, Justo Núñez, opened the debate and gave the floor to the Bishop of Buenos Aires, Monsignor Benito Lué y Riega, who masterfully expressed the thesis of Spanish supremacy over the Creoles, in these terms: "There is not only no reason to make a novelty with the Viceroy, but even if there were no part of Spain left that was not subjugated, the Spaniards who were in America should take and resume command of them, and that this could only come into the hands of the country's children when there was no longer a Spaniard in it. Even if there were only one member of the Central Junta of Seville left and he arrived on our shores, we should receive him as the Sovereign." This inflamed the spirits of the patriots.

The royalists had played their strongest card. It was the word of the city's spiritual leader, against which few dared to rise. At this critical moment of the debate, the patriotic eyes converged on the only one capable of refuting their arguments, with solvency. It was Juan José Castelli, the "Voice of the Revolution," a magnificent orator, and who, as a lawyer, had reversed processes considered "lost" in advance. Castelli accepted the challenge and argued that, with the fall of the Central Junta of Seville, the Sovereign Government of Spain had expired. The Regency Council of Cádiz lacked authority over America, as the Americans had not delegated any authority to it. Consequently, in the absence of the King, the people of Buenos Aires should reassume their full sovereignty and decide who would govern them, as was done in the Peninsula. Therefore, there was no difference between European and American Spaniards; since they had not engendered "rams" in our lands, but people equal and with the same rights as the peninsulars; in obvious response to the Bishop's thesis. In response to this, Lué managed to respond that he had not come to this assembly to debate with anyone, but simply to freely express his opinion on the matter that summoned them.

The old sailor Pascual Ruíz Huidobro, hero of the English Invasions, held the obvious argument that the Viceroy represented the King. Without a King, he had no one to represent; and consequently, he should cease in command, and the Cabildo should assume in his place.

The royalists replied through Prosecutor Manuel Villota, arguing, quite logically, that the city of Buenos Aires did not represent the entire Viceroyalty; and that it could not decide for all the provinces. Consequently, nothing could be solved without consulting them beforehand. In response to this reasonable objection, Juan José Paso argued that Buenos Aires acted, in this act, as an "older sister" watching over the other provinces, which would later be invited to join the new Junta to be appointed.

Cornelio Saavedra proposed a formula too moderate for the taste of many: to delegate the Government to the Cabildo, until it constituted a Junta, in the form it deemed convenient. Since Cisneros still had much influence over the Cabildo, this motion did not fully convince the patriotic side. Saavedra concluded that "there is no doubt that the people are the ones who confer authority or command."

Faced with the risk of losing the vote with the dispersion of votes, the patriotic side decided to support Saavedra's motion; which turned out to be the winner. Once the votes were counted, 158 were for the removal of the Viceroy, in its various forms, 67 voted for his permanence, and 26 did not vote or withdrew before the election. As a curiosity, it can be noted that almost all the priests who voted after their superior, Bishop Lué, did so in favor of Saavedra.

Having triumphed in the Saavedrist motion, the Cabildo proclaimed: "After the most thorough examination, it results that His Excellency the Viceroy must cease in command, and this falls provisionally on His Excellency. Cabildo until the erection of a Junta to be formed by the same His Excellency Cabildo, in the manner it deems convenient."

The councilors Manuel de Anchorena and José de Ocampo were in charge of notifying Don Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros that he had ceased to be the last Viceroy of the Río de la Plata.

More posts: