Saying that Milei devalued by lifting the cap is pure intellectual diexcelledsty

Freeing the dollar in a context of fiscal and monetary balance doesn't imply a forced depreciation

In the Argentine public debate, a conceptual confusion persists: many believe that removing the currency control and allowing the exchange rate to float automatically equates to a devaluation. But this association is technically and economically incorrect. Devaluing implies a discretionary decision by the State or the Central Bank to increase the official exchange rate in a nominal leap, that is, a forced depreciation of the peso set by policy.

On the contrary, freeing the exchange rate in the context of a floating market means that the dollar's price is determined by supply and demand, without artificial fixing or an abrupt leap imposed from power. Therefore, if there is no discretionary decision to modify the official exchange rate, but rather a convergence toward the price already reflected in the informal market, there is no devaluation in technical terms: there is a realignment of relative prices.

The central point is that the real value of the dollar has already been assimilated by the market through parallel channels like blue, MEP, and cash with settlement, which for months have reflected an exchange rate closer to equilibrium. Freeing the exchange rate doesn't create a new price, but rather legalizes and unifies the values that already exist in the real economy. In other words, the devaluation has already occurred, but it happened outside the official circuit. Exiting the currency control is not devaluing: it is ending the fiction of a subsidized and politically manipulated exchange rate.

There is no devaluation pressure when there is macroeconomic balance

A devaluation is usually the consequence of structural imbalances, such as monetary issuance without backing, chronic fiscal deficit, or loss of international reserves. But the current economic policy framework has eliminated monetary issuance to finance the deficit, achieved a financial surplus, and accumulated reserves.

These solid macroeconomic essentials reduce and in many cases eliminate the structural pressure on the exchange rate. Therefore, not only is there no need to devalue, but there are conditions for the real exchange rate to remain stable or even appreciate gradually, based on greater confidence and predictability.

To all this is added a key point: the exchange rate is not a political symbol or an objective in itself, but just another price in the economy. Like any price, it must arise from the free interaction between supply and demand. When the exchange rate is manipulated, deep distortions are caused: currency shortages, incentives for evasion, under-invoicing of exports, over-invoicing of imports, and a real loss of competitiveness. Freeing it is not devaluing; it is allowing the economy to function without hindrances, with clear signals and real prices.

The classic liberal critique of exchange controls

From the Austrian School of Economics, exchange controls like the currency control have been systematically denounced as one of the most distorting and authoritarian mechanisms in monetary matters. Friedrich Hayek, in The Road to Serfdom, warns that price and exchange controls are typical instruments of interventionist regimes that seek to manipulate economic behavior through coercion, generating unintended consequences such as the black market, corruption, and scarcity. Ludwig von Mises was also blunt: exchange controls are incompatible with a free and functional economy, as they interrupt the price discovery process and break the incentives to produce, invest, and trade.

In this context, the elimination of the currency control is not just a technical measure: it is a political and philosophical act of great depth. It means trusting the market again as a system of social coordination, returning monetary sovereignty to citizens, and dismantling decades of centralized manipulation. Ultimately, it is about restoring economic freedom and the spontaneous order that allows prices, including the exchange rate, to reflect real information, not bureaucratic whims.

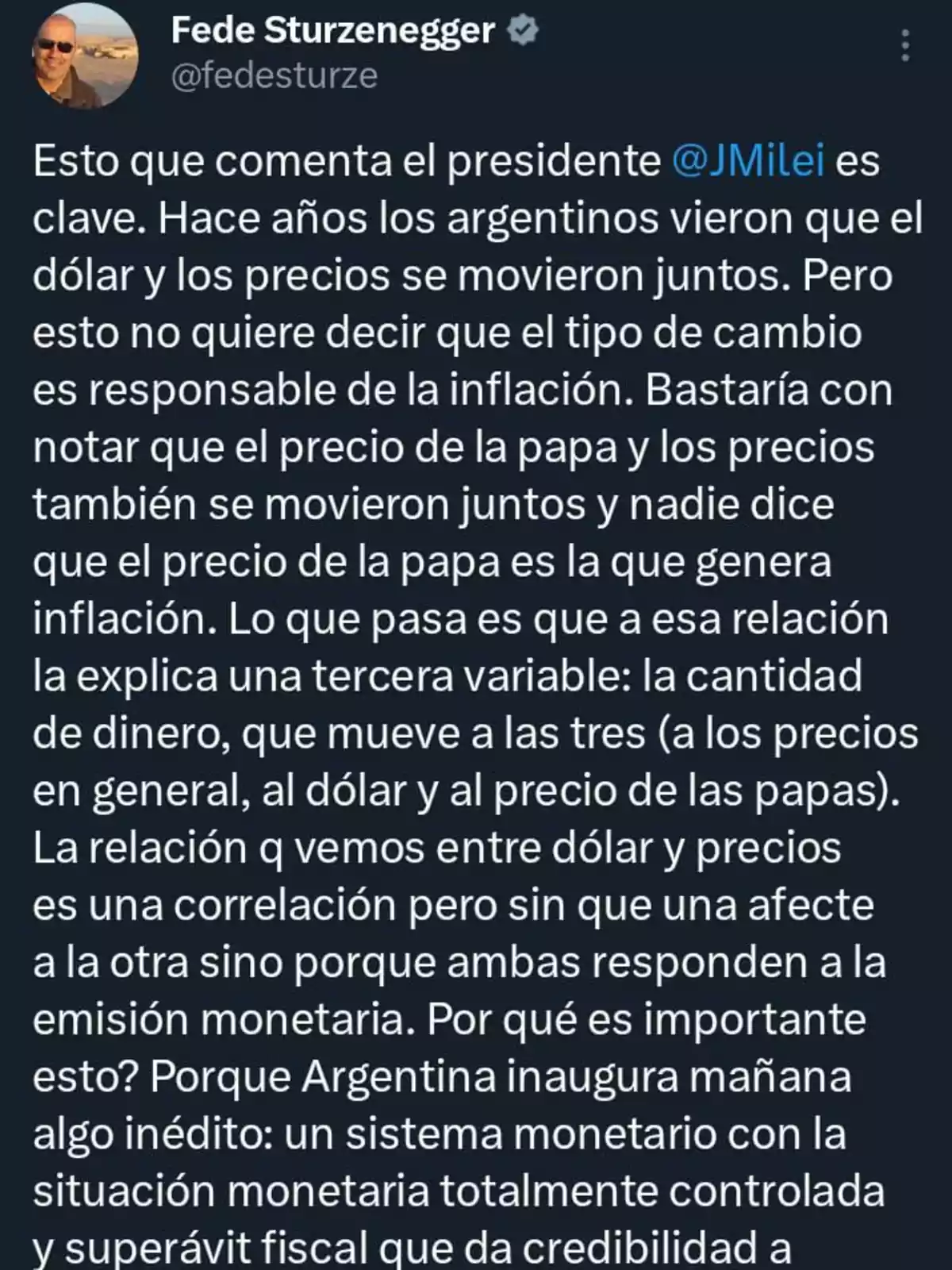

A key lesson: the dollar doesn't generate inflation, issuance does

In a recent post on X, Minister Federico Sturzenegger clearly summarized this phenomenon. Years ago, Argentines saw that the dollar and prices moved together. But this doesn't mean that the exchange rate is responsible for inflation, he explained, adding a precise analogy: It would be enough to note that the price of potatoes and prices also moved together, and no one says that the price of potatoes generates inflation. What unites all these prices is a common variable: the amount of money. It is this, not the dollar, that determines the general price level. This explanation dismantles one of the most entrenched myths of the Argentine economy: that the dollar is the engine of inflation. In truth, inflation, the exchange rate, and the price of potatoes respond to the same cause: monetary expansion. Therefore, in a context like the current one, with a fiscal surplus and zero monetary issuance, there is no reason for dollar movements to have a direct impact on the general price level.

The lesson is compelling: when the monetary base is controlled, prices lose volatility, even if the exchange rate moves. Therefore, the exit from the currency control under these conditions not only doesn't imply a devaluation, but it will be an empirical demonstration that the true anti-inflationary anchor is not the exchange rate, but monetary and fiscal discipline.

As Sturzenegger pointed out, Argentina is late to the club of normality, but it is finally entering. Without shortcuts, without speculations, simply doing what had to be done.

More posts: