What happened on July 9, 1816: the history of Argentina's Independence Day

Everything you need to know about the Congress of Tucumán and the signing of the document that changed history

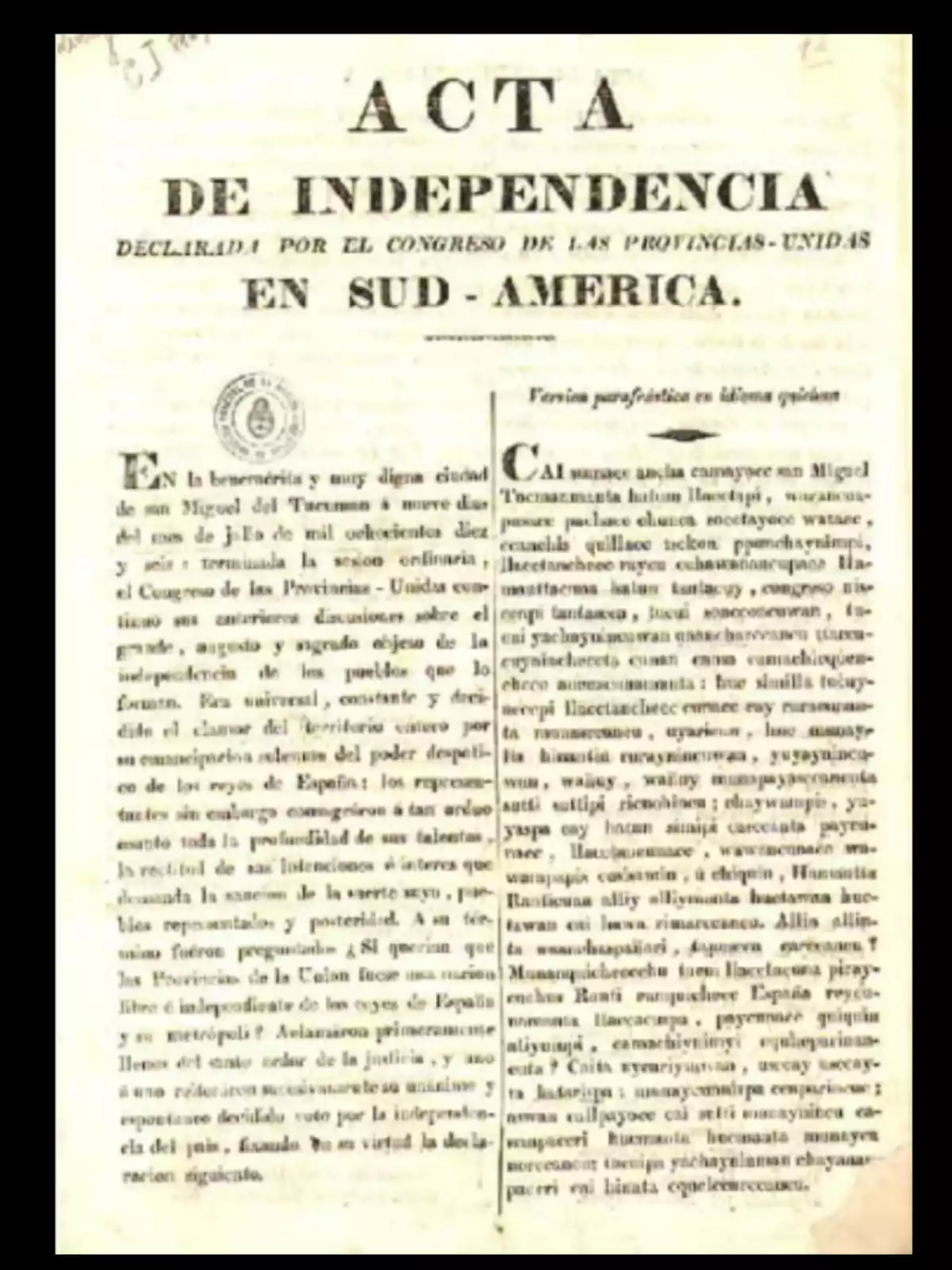

On Tuesday, July 9, 1816, under a winter sun in the city of San Miguel de Tucumán, a group of representatives made a decision that would forever shape the destiny of what is now Argentine territory. That day, in a colonial house that would later be known as the Casa Histórica, the Act of Independence was signed.

The United Provinces of the Río de la Plata formally declared their emancipation from the Spanish monarchy and renounced any other form of foreign domination. The event was celebrated as the culmination of a process that had begun years earlier, in the context of the May Revolution of 1810.

The path to independence

Although the first cry for freedom had erupted in 1810, there was no immediate consensus on how and when to formally break ties with Spain. Political tensions became evident between those who demanded a radical change, such as Mariano Moreno and his followers, and those who advocated for a more gradual transformation, such as Cornelio Saavedra.

Revolutionary ideas coexisted with diplomatic fears. The international context, shaken by the fall of Napoleon and the resurgence of European monarchies, was not favorable to openly republican movements. For this reason, internal discussions extended until 1816.

That year, Ignacio Álvarez Thomas—who had assumed the role of Supreme Director in place of José Rondeau—convened a General Constituent Congress in Tucumán, hoping to achieve a political definition.

The historic July 9 and the debate over the form of government

The Congress met in the house of Francisca Bazán de Laguna, which in 1941 was declared a National Historic Monument. Most of the representatives favored a constitutional monarchy, a model predominant in Europe. The republic, at that time, was a rarity that had only prospered in the United States.

According to accounts from the time, the session began around two in the afternoon. The deputy from Jujuy, Teodoro Sánchez de Bustamante, proposed addressing the issue of independence. The secretary, Juan José Paso, then posed the decisive question: "Do you wish that the Provinces of the Union be a free and independent nation from the kings of Spain and their metropolis?"

The response was unanimous. Thus, the Act of Independence was signed, proclaiming the end of the bond with the Spanish crown.

Beyond Spain: the rejection of any domination

Ten days later, on July 19, Pedro Medrano—deputy for Buenos Aires—proposed a key amendment. Amid rumors that some sectors sought to hand the country over to the rule of Portugal or England, he promoted the inclusion of a clause that made it clear that independence was also from any foreign power.

The phrase "from all foreign domination" was then incorporated into the Act. The congressmen knew that Europe viewed any revolutionary movement with suspicion, so they also drafted an additional document: "End of the Revolution, beginning of Order," a formula that sought to demonstrate moderation in the eyes of the world.

More posts: