Uruguay: a mercantilist country closed to the world that simulates economic freedom

The State must guide foreign trade to protect productive activities

In Defense of Freer Trade

The recent tariff measures promoted by President Trump (which can be presumed to be part of a temporary negotiation strategy and not his long-term goal) have highlighted the multiple regulations that many governments, including ours, have accumulated over time.

Regardless of whether the current tariffs are part of a negotiation tool, we can conclude that if applied permanently, these policies would be highly detrimental to the global and local economy by restricting free exchange and making goods and services more expensive.

The stated goal of these measures is to achieve a positive trade balance with each country, exporting more than is imported. In 2024, according to OEC-World, Uruguay had a trade deficit with the United States: we exported goods worth US$ 1.192 billion and imported US$ 1.213 billion.

Uruguayan Mercantilism: An Obstacle to Growth

Uruguay is not immune to mercantilism. Although our current trade balance is in deficit with the U.S., it doesn't necessarily reflect any a priori inconvenience, as the services section and trade with other countries are not considered here.

However, a limited productive structure can be evidenced, as expected, in a highly intervened economy with low per capita capital accumulation.

According to Central Bank data, between 2014 and 2019, private capital formation decreased by around 28% in relative terms compared to 2013.

In 2024, we mainly exported beef, meat by-products, cellulose, and wood, while we imported oil, diesel, medicines, and agricultural machinery. Although exports grew by 14.6% in the last five years.

Mercantilism, dominant between the 15th and 17th centuries, promoted the accumulation of wealth through trade surpluses, discouraging imports with tariffs and regulations.

Today, Uruguay partially keeps this mindset, with policies that protect specific sectors but limit innovation and competitiveness. As Adam Smith warned in The Wealth of Nations, these restrictions hinder economic growth and impoverish society by reducing consumer choices and making goods more expensive.

Article 50: A Constitutional Lock

A clear example of this mercantilist vision is Article 50 of the Uruguayan Constitution, introduced in 1967 under the influence of CEPAL's import substitution model.

This article establishes that the State must guide foreign trade to protect productive activities aimed at export or that replace imports.

In practice, this has justified regulations that make imported goods more expensive and limit citizens' freedom to choose where and what to buy, perpetuating inefficiencies in the local economy.

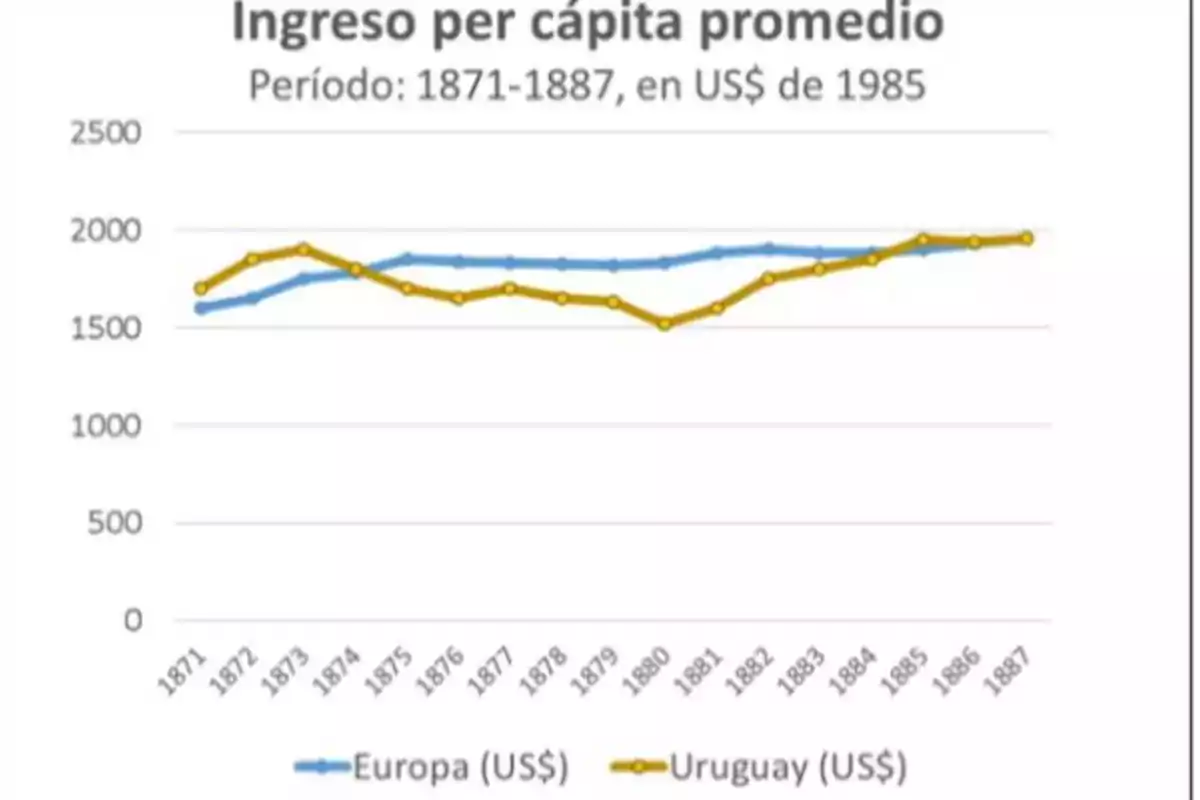

In the past, Uruguay demonstrated that a different model is possible. At the end of the 19th century, thanks to a sound currency, free banking, and an open economy, our GDP per capita exceeded the European average between 1871 and 1887, according to data from Ramón Díaz present in the following table.

This period of prosperity, driven by the liberal constitution of 1830, contrasts with the current restrictions that hinder our potential.

Global Protectionism: A Wrong Path

Globally, measures like the 15% Global Minimum Tax on Profits, agreed upon in 2021 by the OECD and the G20, reflect a trend toward fiscal uniformity that limits tax competition between countries.

Uruguay, by joining this agreement, cedes fiscal sovereignty and restricts its ability to attract investments, perpetuating a sluggish and dependent economy.

Protectionism, whether in the form of tariffs or regulations, stems from the mistaken idea that trade is a zero-sum game, where one wins only if another loses.

However, free exchange benefits all parties by allowing each to specialize in what they do best.

Restricting trade is like prohibiting citizens from shopping at the supermarket because we don't produce everything we consume: it reduces well-being and pushes us toward forced self-sufficiency.

Conclusion

Mercantilism, classic or modern, remains alive in the economic policies of many countries, including Uruguay.

Its logic limits individual and economic freedom in the name of a supposed national interest; it has proven to be inefficient and counterproductive.

Do you think protectionist policies are the solution for economic development, or should we bet on freer trade?

You can see more details of the article and leave your opinion in the comments section at economiasinfrontera.online

More posts: