Kicillof's communism has the third highest IIBB and breaks the Fiscal Consensus

The average provincial tax rate is 3.36%, but Buenos Aires even exceeds the 3.74% established by the Fiscal Consensus

The Gross Income Tax, the main source of funding for Argentine provinces, continues to show marked differences between jurisdictions and a trend that clashes with the national government's goal of reducing the tax burden.

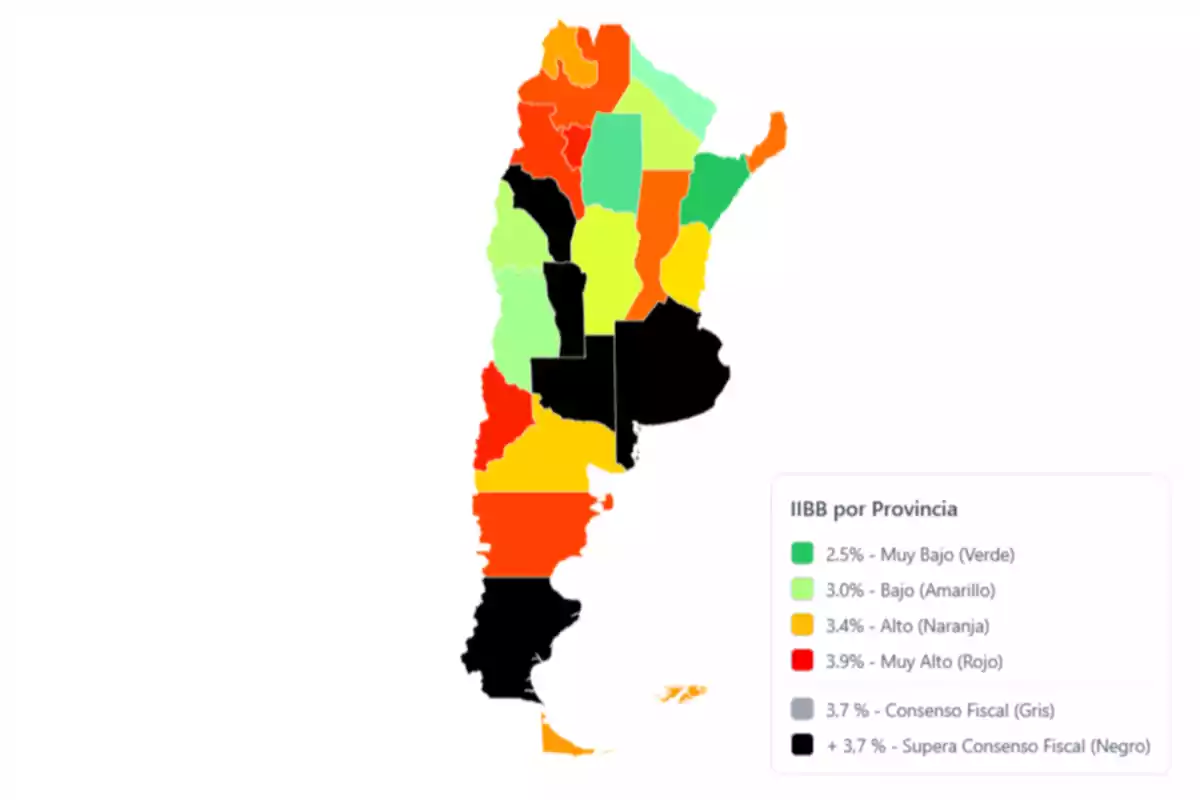

According to data from the Fiscal Competition Monitor, the average rate applied in 2025 to all economic activities is 3.36%, with a range from 2.48% to 3.92%. This provincial tax, which is regressive and distortive in nature, continues to affect companies' profitability and punish workers who depend on them.

In particular, Buenos Aires ranks as one of the jurisdictions with the highest tax pressure, with a rate reaching 3.78%, even surpassing the 3.74% agreed upon in the Fiscal Consensus.

Under the leadership of communist Axel Kicillof, the country's most populous district has chosen to deepen the burden on the private economy with the goal of raising more funds, not to allocate them to education or health, but to finance bureaucratic structures such as the Ministry of Women and gender programs, which President Javier Milei himself has described as part of the "useless" spending that keeps provinces in a state of "fiscal degeneration".

At the upper end, Santa Cruz (3.92%) and La Pampa (3.87%) are also found, two jurisdictions that have historically depended heavily on revenue sharing and an oversized state structure to sustain their finances.

These taxes not only reduce the room for maneuver for SMEsand large companies, but also directly impact employment, investment, and consumption. By increasing the cost of production, they discourage economic growth, drive away new investments, and ultimately crush the purchasing power of workers who depend on a suffocated private economy.

Meanwhile, provinces such as Corrientes and Santiago del Estero have opted for a more moderate tax pressure (2.63% and 2.48% respectively), while Buenos Aires insists on maintaining a revenue model that, far from promoting development, consolidates an oversized and inefficient state apparatus.

In a context where the national government seeks to eliminate distortive taxes and put an end to decades of fiscal plundering, the decision of the donkey Kicillof represents a direct challenge to Milei's economic cleanup policy. For "decent workers" and companies that generate real employment, high rates are nothing but an obstacle to any possibility of progress.

More posts: