In the midst of "democracy," and weeks before a key election, Raúl Alfonsín signed a decree that allowed the detention without trial of 12 people —among them, Rosendo Fraga— for merely expressing opinions that his government considered "destabilizing." A silenced episode of recent history, where freedom of expression was the main victim.

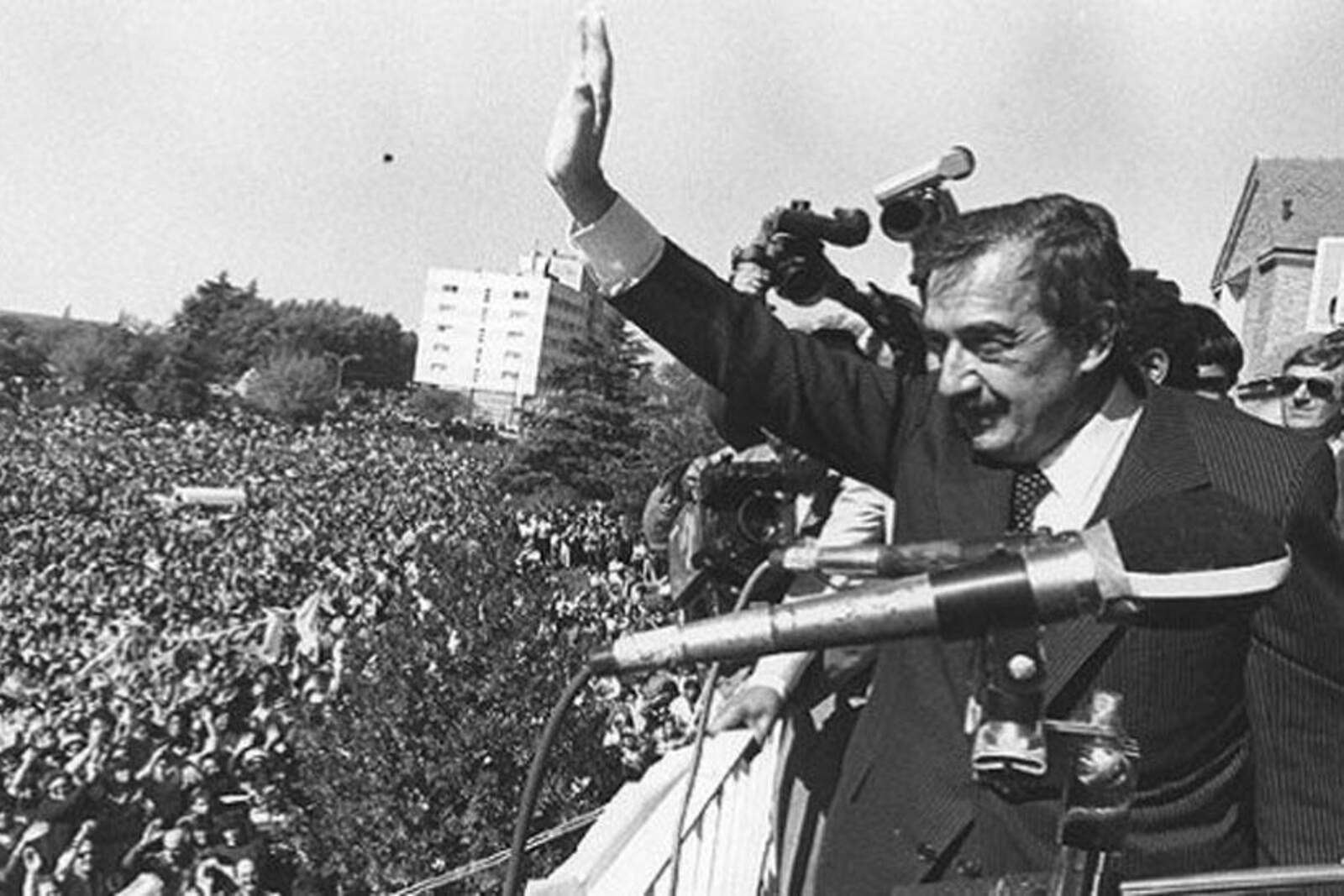

In October 1985, Argentine democracy was experiencing one of its toughest tests since institutional recovery. Amid a climate of bomb threats, military tension, and political maneuvers in the context of legislative elections, President Raúl Alfonsín adopted an extreme measure that today, almost four decades later, continues to cause concern: the arbitrary arrest of 12 citizens —military and civilians— without prior judicial intervention.

[IMAGE]{994773}[/IMAGE]

On October 22, 1985, the radical leader signed Decree 2049/85, ordering the detention for 60 days of six military personnel and six civilians, all accused of participating in an alleged attempt to destabilize the constitutional government. The decision was made without solid judicial evidence and before formally declaring a State of Siege, which left the detentions outside the bounds of current legality.

The measure was ratified three days later, on October 25, when Alfonsín decreed the State of Siege —a figure constitutionally reserved for situations of extreme institutional gravity— and thus consolidated an episode that would be marked as one of the most controversial of his administration.

[IMAGE]{994776}[/IMAGE]

Among the detainees was retired General Guillermo Suárez Mason, a figure linked to crimes during the last civic-military dictatorship, along with other prominent officers: Pascual Oscar Guerrieri, Alejandro Agustín Arias Duval, Osvaldo Rodolfo Antinori, Leopoldo Cao, and Jorge Horacio Granada.

But civilians who had no relation to armed or military actions were also imprisoned. The most well-known was political analyst Rosendo Fraga, now a regular commentator in national media, who at that time was already acting as a consultant and stood out as a critical voice of the radical government. His family heritage —descendant of three generations of military personnel— and his connection with military sectors fueled the suspicions of the government, although he was never proven to have participated in coup maneuvers.

[IMAGE]{994770}[/IMAGE]

Along with Fraga, Daniel Horacio Rodríguez (journalist from La Prensa), Jorge Antonio Vago (director of Prensa Confidencial), Ernesto Raúl Luciano Rivanera Carlés, Enrique Gilardi Novaro, and Alberto Hernán Camps were detained. All were deprived of their freedom without formal accusation or judicial intervention, in a context where freedom of expression seemed to be subordinated to political convenience.

The front page of the Clarín newspaper on October 25 left no room for doubt: "Civilians and military personnel arrested due to the climate of disturbance," it headlined with catastrophic letters. A few days later, 11 of the 12 detainees were released without having been prosecuted. Only Suárez Mason remained longer in preventive detention, due to his direct involvement in cases of crimes against humanity.

Meanwhile, on the same day the State of Siege was decreed and Rosendo Fraga was imprisoned, the Judiciary released actor Norman Briski, who had been detained for three days under suspicions of links with Montoneros. A contrast that reflected the arbitrariness of the government's decisions at that time.

The legislative elections of November 9, 1985, were held with the State of Siege in effect. Despite the tense climate, UCR prevailed with 43% of the votes, consolidating its parliamentary majority. But the institutional price was high: a dangerous precedent was set in which the national Executive acted above constitutional guarantees, silencing dissenting voices under the pretext of preserving order.

Rosendo Fraga, detained for thinking differently, never wanted to talk much about the subject. Years later, his figure would be consolidated in the academic and media world, even making headlines in the entertainment world when he married actress Mónica Gonzaga, an icon of national cinema in the '80s. Today, 39 years after that event, it is worth remembering that within the system imposed by 'the father of democracy' they turned a blind eye to the imprisonment of citizens without prior trial or concrete evidence.