Javier Milei and the return of natural law versus modern legal positivism

How the natural law tradition gains new life in the philosophical-political crusade of liberalism in Argentina

Javier Milei's emergence on the Argentine political scene and his rise to the presidency represent, more than a simple reaction to economic statism, a theoretical and philosophical revolution in the conception of the legal and social order. What is at stake in his crusade is not only the size of the State, but the very foundation of law: is law an arbitrary creation of political power or the rational discovery of preexisting norms that must limit power?

This debate is not new. Since the time of Socrates, Western tradition has oscillated between two opposing conceptions of law. On one hand, positive law, which sees legality as the expression of sovereign will, whether of the monarch, the people, or the legislator, without necessary reference to justice. On the other hand, natural law, which holds that there are objective and universal moral principles that precede any human legislation, and that every law must respect in order to be legitimate.

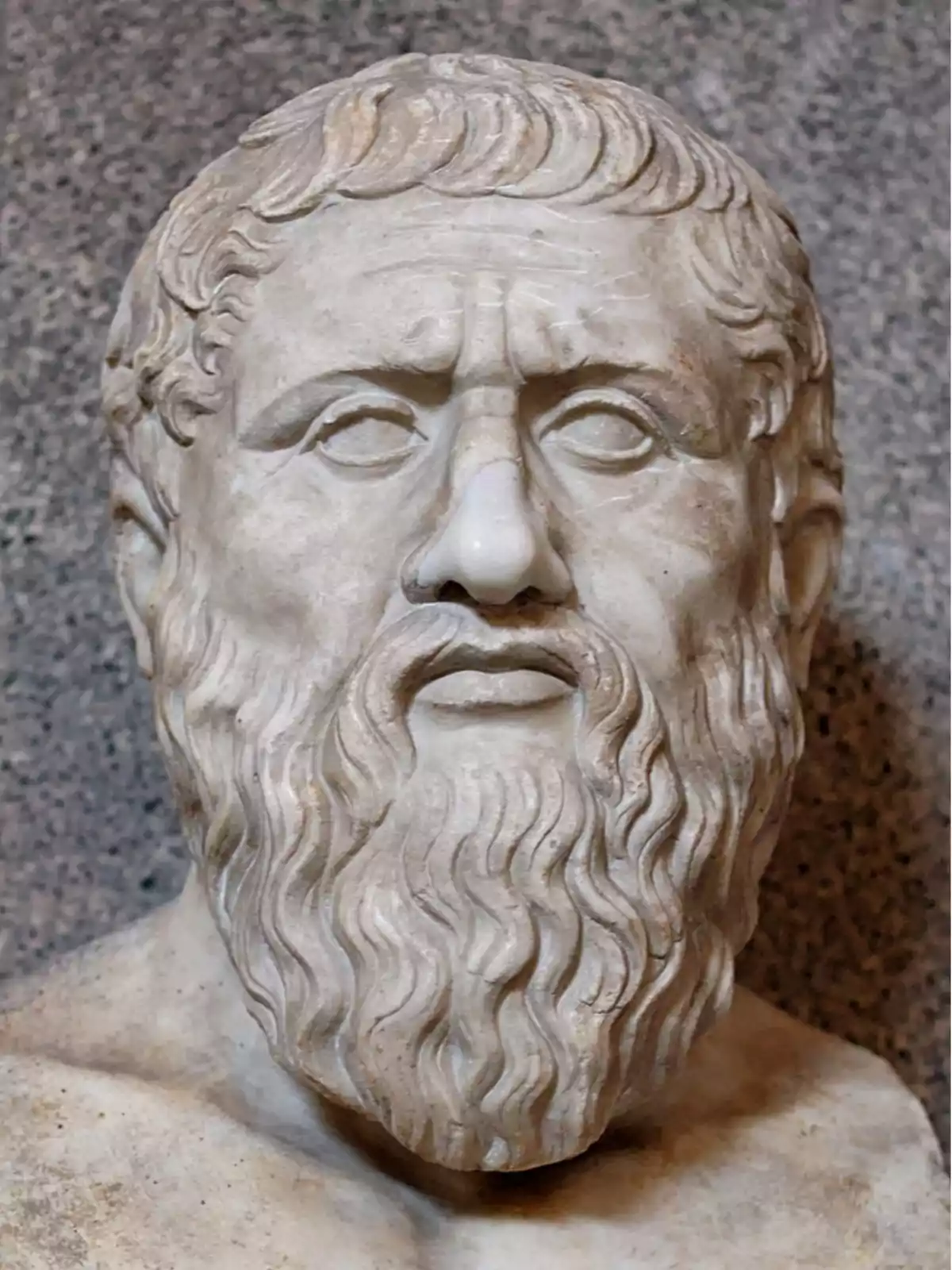

From Platonic Absolutism to the Libertarian Revival

The statist tradition in Plato, who, influenced by the Spartan order, conceives law as an instrument of social engineering intended to shape citizens according to a collective ideal. In The Republic, Plato describes a hierarchical State, where individuals are not ends in themselves, but functional parts of a social body led by an enlightened elite. In this context, law is not limited to protecting rights, but imposes ends, structures social classes, and controls all aspects of life. This rationalist and totalizing vision finds its continuity in authors such as Rousseau, Hegel, and Kelsen, who see the State as the source of legal legitimacy, displacing any notion of natural justice.

Socrates, as he appears in the dialogue Crito written by Plato, adopts a clearly favorable stance toward positive law. Despite having been unjustly condemned, he rejects the proposal to escape from prison, arguing that breaking the law, even an unjust law, would be equivalent to corrupting the soul and harming the polis. According to Socrates, having lived his entire life in Athens and having benefited from its laws, he has entered into a tacit pact with the city. Therefore, disobeying his sentence would violate that implicit contract, weakening the legal order. This defense of unconditional obedience to the established order reflects a conception of law as legitimate authority in itself, independent of its moral content.

But it is with the School of Salamanca, and later with modern libertarian thinkers, that natural law acquires a systematic structure: law is not a decree of the sovereign, but a set of principles deducible from the rational nature of man, centered on life, liberty, and property.

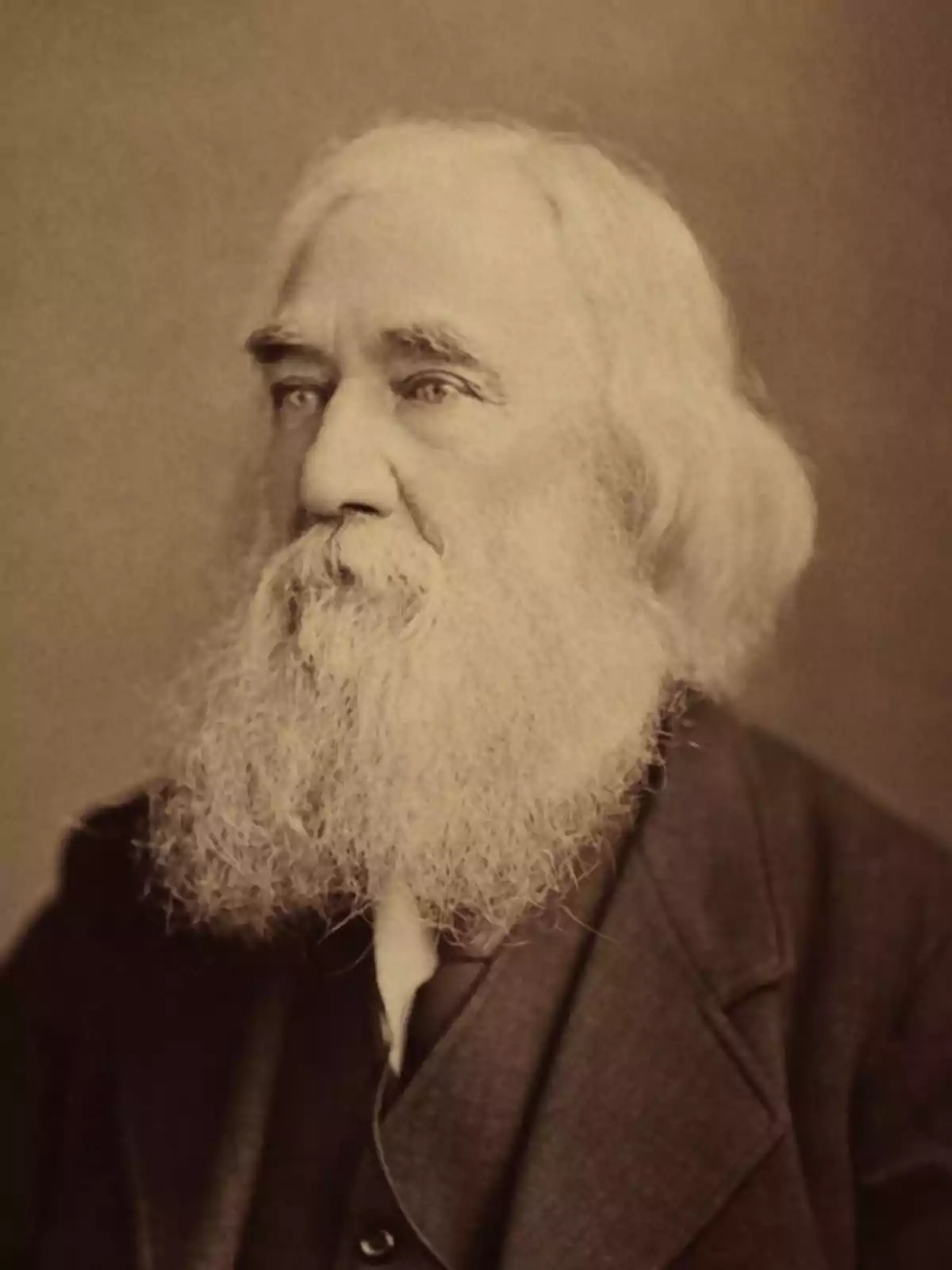

Authors such as Lysander Spooner were radical in this defense. For him, any legislation that contradicts the principles of natural justice is illegitimate, and no social contract can bind anyone who has not explicitly consented. In his critique of the United States Constitution, Spooner argues that voluntary consent and the absence of coercion are the only valid sources of legal obligation, which essentially nullifies the legitimacy of political power as it has been historically exercised.

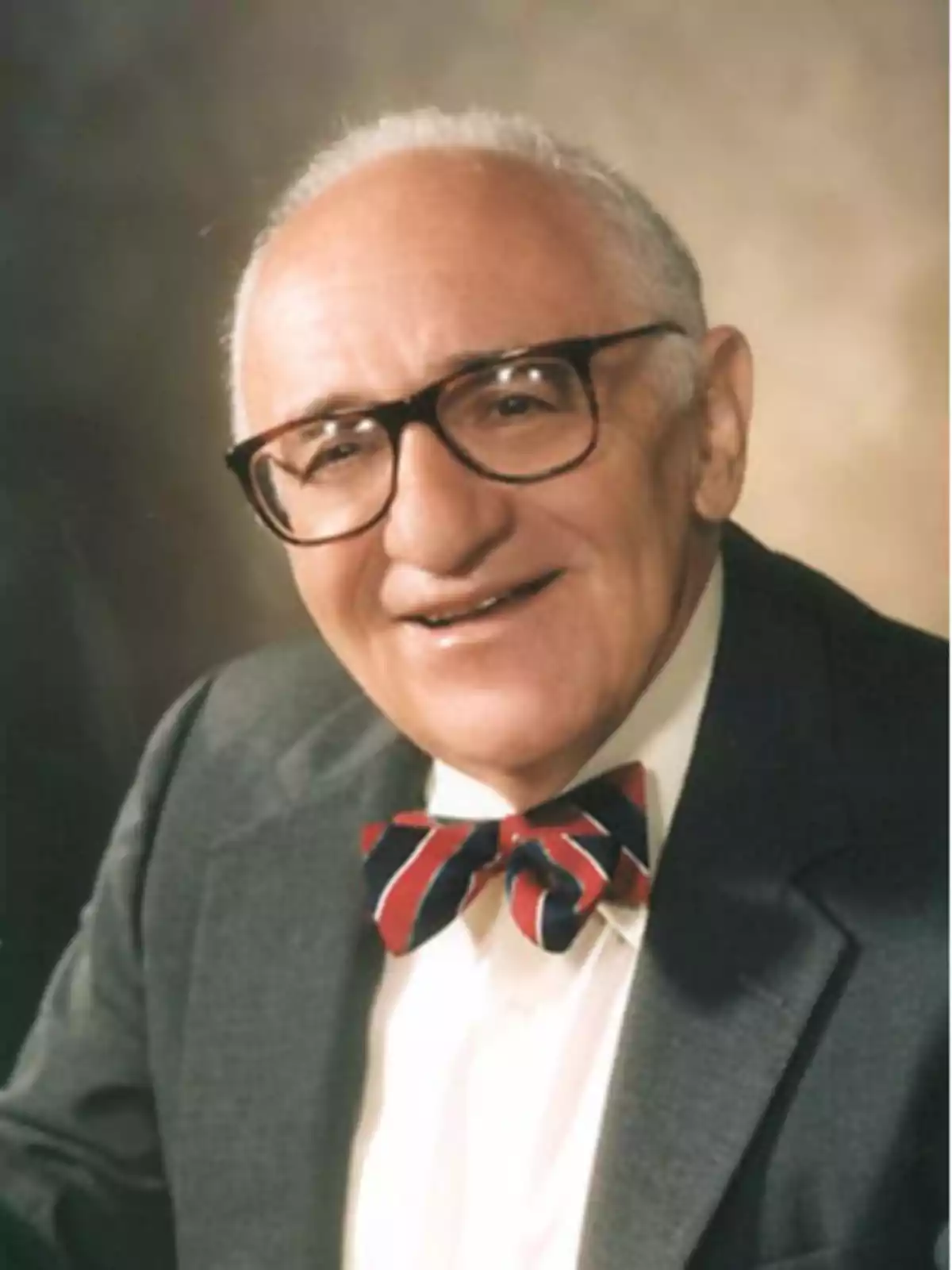

This tradition is joined by Murray Rothbard, who develops a complete legal ethic based on self-ownership and the original appropriation of scarce resources. In his view, all just law derives from the non-aggression principle, and the State, by exercising systematic violence through taxes, regulations, and monopolies, becomes an illegitimate structure. For Rothbard, law is not created, it is discovered, and its function is not to organize society but to protect individual liberty.

Rothbardian thought is complemented by Hans-Hermann Hoppe, who, from argumentative logic, demonstrates that any attempt to justify aggression is performatively contradictory. Libertarian ethics thus becomes the only morality consistent with the nature of rational discourse. This structure is reinforced by the work of Jesús Huerta de Soto, who recovers the Thomist-Scholastic tradition and fuses it with Austrian praxeology to defend a spontaneous legal order, where justice is defined as absolute respect for legitimately acquired property.

The Non-Aggression Principle as the Foundation of Law

This tradition of radical criticism of power is not exclusive to the West. Philosophers of political Taoism, such as Lao Tse, Chuang Tzu, and Pao Ching-Yen, reached parallel conclusions more than two millennia ago. Lao Tse maintained that government, by exercising its power, corrupts the natural behavior of the individual and generates disorder where there is spontaneous harmony. Pao Ching-Yen went further: he asserted that the State institutionalizes violence, stimulates theft and banditry, and subjugates the weak for the benefit of the strong. This Taoist critique of political coercion, developed centuries before Hobbes or Rousseau imagined the social contract, is surprisingly aligned with the non-aggression principle formulated by modern libertarians.

It is within this tradition that Javier Milei is situated. Not as a theorist, but as a politician who seeks to operationalize in political praxis the essential principles of natural law. His uncompromising defense of private property, his denunciation of the State as a coercive apparatus, his explicit admiration for Mises, Rothbard, and Huerta de Soto, and his repeated use of the non-aggression principle are not mere rhetorical references: they constitute the doctrinal core of his political project.

Far from being a reformist technocrat, Milei is proposing a complete inversion of the contemporary legal paradigm. Instead of seeing law as an instrument of the State to impose collective ends, he conceives it as a moral limit on the use of force, even (and especially) when it is exercised under legal appearance. His diagnosis of Argentina, as a country devastated by the political "caste" that has colonized law to plunder the productive citizen, is inseparable from his philosophical conception of law: what fails is not only the economy, but the ethical foundation of the normative order.

In this sense, Milei is reviving a liberal vision of law: the idea that law must protect rights, not create them; limit power, not expand it; emerge from the individual, not from the collective. This vision aligns perfectly with the tradition of Spooner, Rothbard, and Huerta de Soto, and stands in stark contrast to the Platonic legacy of the educating, redistributive, and planning State.

Thus, what is at stake in Milei's government is not just fiscal adjustment or market liberalization. It is a philosophical restoration of law as a moral field prior to the State, a recovery of justice as an objective limit to all coercion, and a revaluation of the individual as a sovereign subject in the face of any political structure.

History, and especially the history of legal thought, will remember this moment not only for its economic reforms, but for its attempt to resurrect natural law in times of positivist hegemony. In a world where legality has been divorced from justice, Javier Milei represents a powerful anomaly: a politician who doesn't want to legislate more, but to delegitimize unjust legislation; not to conquer the State, but to dismantle its capacity to violate moral law.

More posts: