Anniversary of the Battle of San Nicolás: The baptism of fire of the Argentine Navy

This naval confrontation marked the baptism of fire for the nascent Argentine Navy.

At the beginning of 1811, the Junta Grande prepared three small vessels, under the command of the Maltese sailor Juan Bautista Azopardo, to deliver aid and supplies to General Manuel Belgrano, who was engaged in his Campaign to Paraguay.

Informed of this maneuver, a royalist squadron set out from Montevideo to intercept the patriot flotilla, commanded by the frigate captain Jacinto de Romarate Salamanca; a 36-year-old Basque; who had participated in Europe in naval actions against the French Revolution in the Mediterranean; and had been a hero in the fight against the English.

He was a skilled sailor; who was only defeated by Admiral William Brown, with the fall of Montevideo, three years later.

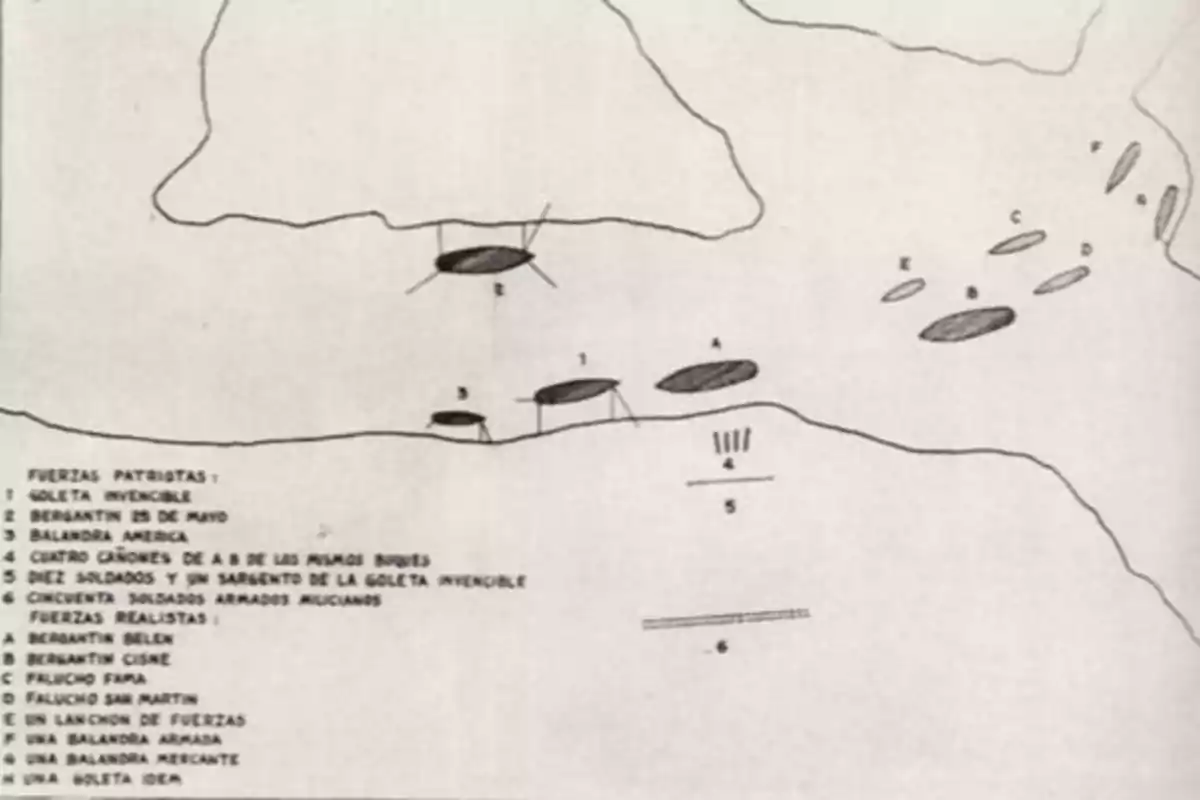

Romarate commanded two brigs: the "Cisne," with 12 cannons, under the command of frigate lieutenant Manuel de Clemente, which was his flagship, and where his pennant flew; the "Belén," with 14 cannons, led by frigate lieutenant José María Rubión, the sloop "San Martín," led by ensign José Aldana, the sloop "Fama," captained by ensign Joaquín Tosquella; the sumaca "Aranzazú," and two more smaller ships. Each sloop had one cannon.

Both fleets sight each other: Romarate's plan

With the dawn of February 28, 1811, both squadrons were spotted in the Paraná, a few kilometers downstream from the town of San Nicolás. Romarate then summoned his officers to a War Council. In it, they decided to enter the channel formed between the coast of San Nicolás and the island opposite.

On both sides, Azopardo had placed his ships, with their cannons ready to face the enemy in crossfire. The problem was that the royalists would be forced to sail against the current, which at that point has a lot of flow and speed.

This meant slow navigation between the patriot cannons. But it also represented an advantage: since the royalist ships were better armed. Additionally, their crew was better trained to fire more quickly than the patriots, and their cannons worked well; unlike Azopardo's.

Consequently, they decided to attack against the current, advance slowly, and take advantage of the slowness to subject the patriots to more cannon fire from both sides of their brigs, passing between the patriot ships. As the wind was not blowing, at noon, Romarate anchored about "two cannon shots" (between 1.5 km to 2 km) from Azopardo's positions.

Romarate's ultimatum

With both squadrons facing each other, Romarate, from the "Cisne," fired a cannon salute and sent a boat with a parliamentarian (the commander of the "Fama") toward the patriot corvette "Invencible"; where Azopardo was located. The boat did not reach its destination, as the patriots threatened to sink it.

Then, the boat returned to the "Cisne" without being able to deliver a document issued by the royalist leader Javier Francisco de Elío, in which he labeled the revolutionaries as "rebels... part of a sedition... enemies of order"; and declared traitors those who obeyed the "subversive" Junta.

Along with this decree, Romarate joined an ultimatum to Azopardo, to surrender within 2 hours, for reasons of humanity.

As absolute calm reigned, the contenders remained so until dawn. Then, Azopardo hoisted a red flag on his foremast, a sign that he would neither give nor ask for quarter; while Romarate sent a boat to scout the patriot positions; which suffered some shots. Due to lack of winds, everything remained so until the dawn of Saturday, March 2, 1811, which dawned with a south wind.

The first phase of the Combat

Knowing they were ready for combat, both flotillas activated preparations. At 8 in the morning, the brigs, followed by the two royalist sloops, began to enter the channel, between the corvette "Invencible" on one side, and the brig "25 de Mayo" on the other side. Thus began the heavy fire, both from the shore, by the 4 cannons stationed there, and between the ships.

As the channel was very narrow, to avoid being dragged to the shore, the royalists furled some sails. Despite this, both brigs ran aground on a bank near the island; from which the "Belén" managed to free itself, due to the skill of its crew.

The "Cisne," meanwhile, remained stranded, enduring the fire from the patriot coastal battery, which opened 4 holes in its hull, and others in its sails (rigging). Desperately maneuvering, in the end, the "Cisne" also managed to free itself.

At that providential moment, the patriots lost the opportunity to immediately attack the stranded ships. Some believe it was due to indecision, cowardice, or inexperience on the part of the crew. However, it is more sensible to think that Azopardo preferred not to risk the secure position where he had established himself.

The second phase of the action

After making some minimal repairs, the royalist squadron charged again around 3:00 p.m., with more impetus. The "Belén" headed toward the "Invencible" to board it. The "Cisne," with Romarate on deck, took on the "25 de Mayo," with the support of the two sloops, firing rifles and their cannons.

When the small crew of the patriot sloop "Americana," which had remained (the rest was serving the land cannons) noticed that the entire enemy squadron was coming at them, ready to board, they panicked and abandoned the ship.

Surely the fact that their leader, Ángel Hubac, was serving the land battery and could not manage the situation, had influenced this.

Despite this desertion, Azopardo remained on the deck of the "Invencible," awaiting the final royalist charge. Thus, he and his crew fought valiantly for two hours.

Meanwhile, the "25 de Mayo" was boarded by the "Cisne," aided by the sloops. The brig's crew panicked and began to abandon the ship, despite the valiant efforts made by its commander, Hipólito Bouchard; who, seeing the situation lost, threw himself into the river to avoid being captured.

Meanwhile, the only one still resisting was the "Invencible," with Azopardo on deck; until finally, the schooner was attacked by all the other ships, which had already been freed after dealing with the "25 de Mayo."

It was then boarded by far superior forces, who cornered Azopardo and the few crew members surrounding him against the ship's powder magazine. Following instructions received from the Junta Grande, Azopardo threatened to blow up the ship.

However, the wounded around him begged him not to do so. It was at that moment that the commander agreed to surrender, in exchange for the lives of his sailors being spared; to which Romarate agreed.

The consequences of the battle

Of the 60 crew members of the "Invencible," 41 lay on deck, dead or wounded. Azopardo and 62 survivors were taken prisoner; all the patriot ships were captured and taken to Montevideo.

The land battery, under the command of Angel Hubac, meanwhile, had exhausted every last cartridge and supported their comrades on the ships as much as they could. Militia sergeant Juan Cardoso offered his poncho to improvise "wads" to fire the cannons.

The crew members who escaped (many by swimming), and the leaders Bouchard and Hubac reached Buenos Aires by land. In his report, Romarate said the patriots had more than 40 casualties. There are no records of the royalist casualties; but only the "Belén" had 11 dead and 16 wounded; and severe damage to its hull and masts.

After the defeat, the commander of San Nicolás abandoned his position, guarding the land battery. As the sun set, the royalists disembarked, and without opposition, they scoured the surroundings, took the 4 cannons, without reaching the town.

They stayed a few more days to make minimal repairs. They disembarked several times to gather provisions; until they set course for Montevideo, with their three prize ships.

This battle marked the baptism of fire for the nascent Argentine Navy.

By Juan Pablo Bustos Thames, for La Derecha Diario.

More posts: