Massa left yuan, Milei receives the problem: the deception behind the swap with China

What Massa presented as a reinforcement for the reserves was actually an accounting illusion with real consequences

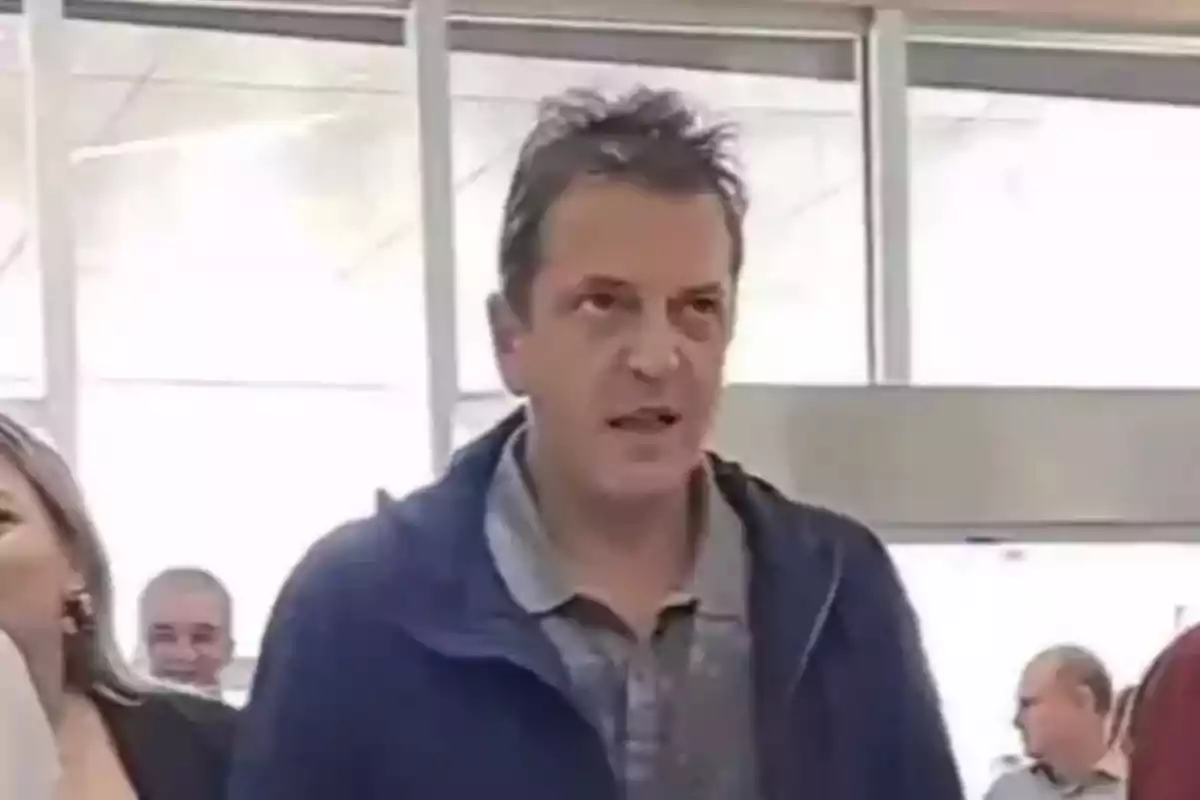

In October 2023, amid a currency run, then Minister of Economy, Sergio Massa, announced the activation of the second tranche of the currency swap with China for the equivalent of 5 billion dollars. It was a reissue of the agreement originally signed in 2009, with subsequent expansions during the Kirchner governments.

At that time, the measure was sold as a pragmatic solution to strengthen international reserves and face imminent payments, such as commitments with the International Monetary Fund. But what seemed like a rescue tool ended up being, in fact, a financial time bomb.

The swap is not, as many assume, a loan in dollars. It is a currency exchange between central banks: the Central Bank of the Argentine Republic (BCRA) delivers pesos and receives yuan, which are added to its gross reserves.

In theory, those yuan can be used for foreign trade operations with China. However, the effective availability is limited, and the quality of those reserves is conditioned by the behavior of the Chinese currency in international markets.

What does a devaluation of the yuan imply?

A devaluation of the yuan implies a loss of value against the US dollar, the currency that remains the global reference for international transactions, reserves, and debt. In a context where China may choose to depreciate its currency to stimulate its exports or to sustain its domestic demand, countries that have assets in yuan —like Argentina— suffer a direct effect on their external balance.

Bilateral swaps usually include compensation clauses for value variation. This means that, at the end of the agreed period, the devaluations of both currencies are compared. The counterpart whose currency has depreciated more must compensate the other. But that coverage is not automatic or immediately available: the damage is already done when the value of the yuan falls and, therefore, its equivalence in dollars within the gross reserves is reduced.

In other words, although Argentina doesn't "lose" the yuan, it does see the accounting valuation of its reserves deteriorate. This is significant: much of the confidence of economic agents —banks, investment funds, multilateral organizations— is based on periodic reports of international reserves.

What happens with Argentina's international reserves?

International reserves are the most important backing of a bimonetary economy like Argentina's. In particular, they allow stabilizing the exchange market, giving confidence to savers, and covering external obligations. But not all reserves have the same value. There is a key distinction between gross reserves (the entire stock of external assets of the BCRA) and net reserves (discounting payable liabilities and unavailable lines).

The swap with China, although it adds to the gross reserves accounting-wise, doesn't automatically translate into effective firepower. First, because it involves yuan, not dollars: many international payments and market operations require liquid dollars. Second, because its availability is restricted to specific purposes, and its conversion to another currency depends on political and financial conditions beyond Argentina's control.

If you add to that a devaluation of the yuan —as has been happening since mid-2023—, the blow is double: the accounting value of those reserves is reduced, and their real utility is further limited. For example, if the BCRA has 35 billion yuan that were worth 5 billion dollars at the time of the agreement, and the yuan devalues by 10%, those same assets now equal only 4.5 billion dollars. The drop is automatic, even if not a single bill has moved.

This mechanism turns the swap into a kind of "accounting trap": it artificially inflates the figures in the short term but introduces a structural fragility that becomes evident as soon as the monetary situation turns adverse.

The political and technical responsibility of Sergio Massa

It was Sergio Massa who signed the activation of this second tranche of the swap in October 2023, amid a financial storm. He did so accompanied by his trusted team, in the context of last-minute negotiations with the People's Bank of China. The decision was justified as a measure to avoid a deeper run and guarantee short-term external payments. But, like any economic policy action, it must be evaluated for its future costs and benefits.

Massa not only accepted a line of credit in yuan —when the underlying problem was the lack of dollars— but did so with a clear electoral motivation. Instead of being transparent about the Central Bank's situation, he chose to artificially inflate the gross reserves, creating an illusion of stability in the eyes of the electorate, investors, and multilateral organizations.

From a technical standpoint, the swap with China did not strengthen the solvency of the Argentine financial system. On the contrary, it tied it to the fluctuations of a non-convertible foreign currency, managed by a central bank that responds to foreign interests. Additionally, the contingent nature of the swap —which can be activated or deactivated according to Beijing's political decision— makes this type of instrument a volatile and vulnerable tool, far from the stability required by the reserves of a serious central bank.

More posts: