Why did the May Revolution break out? The key was in a Spanish city.

The May Revolution broke out after a series of political events in Spain that disrupted the colonial order

Viceroy Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros was aware that since early 1810 there was a tense and adverse atmosphere in the capital. Foreseeing a disastrous outcome in Spain's struggle against Napoleon, the viceroy warned the port authorities of the viceroyalty to intercept any document or publication arriving with unfavorable news from the Peninsula. Cisneros sensed it could further agitate the spirits. Nevertheless, he failed to do anything more, when the most reasonable or sensible action would have been to order the deployment of royalist forces to Buenos Aires, to contain an insurrection that, by this point, was already unstoppable.

Ricardo Levene recounts that, on the evening of May 13, 1810, an English merchant frigate named John Paris arrived in Montevideo, having set sail from Gibraltar, bringing the worst news the viceroy could expect. At this point, Levene disagrees with Cisneros; who claims that the British ships were two, not one.

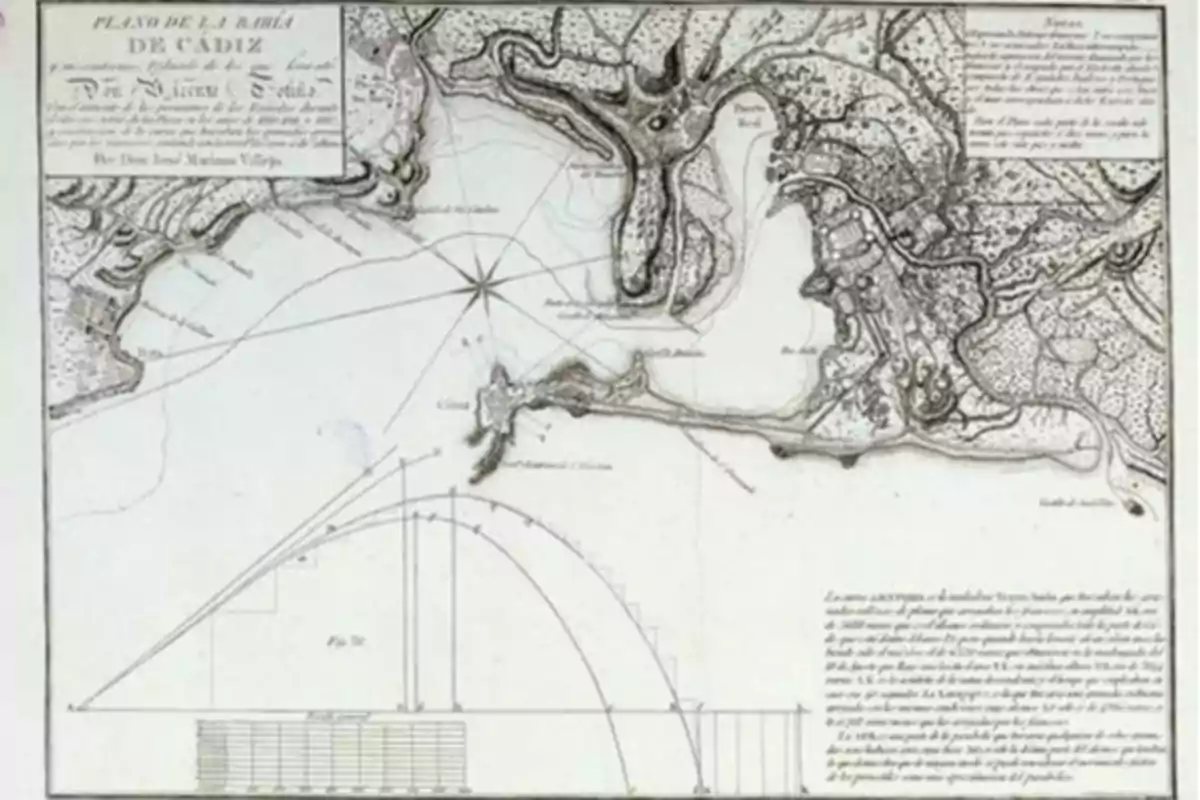

Cisneros had appointed in Montevideo a government composed of Joaquín de Soria as military commander and Cristóbal Salvañach as the first vote mayor. Following the instructions provided by the Viceroy, Soria searched the British vessel and seized the papers it carried. Among them were proclamations announcing the fall of Seville and the dissolution of the Central Junta; the body that had appointed, precisely, Cisneros himself; as well as the creation of the Regency Council in Cádiz. Immediately, both royalist leaders of Montevideo communicated to Cisneros, who resided in Buenos Aires, the news they had just received, with the seized prints containing them.

As a southeast wind affected navigation on the Río de la Plata for forty-eight hours, the news was delayed in reaching Buenos Aires until midday on May 17. As the viceroy received the news, it also spread, becoming the talk of the town.

Given the seriousness of the events, which could not be concealed for long, Cisneros decided to disclose them "in an orderly manner," after much deliberation. He gave the same instruction to military governor Soria, to do so in Montevideo.

The seized publications reported that the French, victors in the Battle of Despeñaperros, occupied all of Andalusia. The people of Seville, exasperated, had risen against the Central Junta. Its members, accused of treason, fled from the popular fury. When they arrived in Cádiz, they were pursued, imprisoned, or deported. Meanwhile, the people of Cádiz created, as if it were a Sovereign Nation, a Regency of Spain and the Indies, to govern in place of the Central Junta all that remained of the shaken Spanish Empire.

An English historian of the time would recall: "When the Central Junta arrived in Cádiz, it encountered the most hostile opposition from the local Junta acting in this port. Lost, not only due to the unpopularity that the disasters had brought upon it, but also due to the lack of means of governance it found itself in, it abdicated its powers to a Regency, composed of five members, among whom were General Castaños and the Mexican Lardizabal, noted as a liberal."

It was the worst news Buenos Aires could receive. It had fallen under the clutches of a city seen as the oppressor of the Río de la Plata capital. Mariano Moreno himself exclaimed upon learning that Cádiz now intended to establish itself as the new seat of the vacant metropolitan throne: "The Nation has been left without any power that can represent the monarch's sovereignty. But the mercantile spirit of the merchants of Cádiz, FERTILE IN SCHEMES TO PERPETUATE US IN THE SAD CONDITION OF A FACTORY, has forged this Regency Council, which intends to impose itself on us, with the characteristics of sovereignty."

This turn of events precipitated the outbreak of the May Revolution; which had been brewing for several months, but for one reason or another, lacked the fuel to ignite it.

Vicente Fidel López, son of Vicente López y Planes, an eyewitness to the events and later author of our National Anthem, contributes: "indeed, the influence and power transferred to the men of Cádiz were synonymous, in Buenos Aires, with the influence and power of the reactionary party that had been defeated by the Patricians on the battlefield, and by 'The Representation of the Landowners', in the field of science and justice. The Regency of Cádiz was, therefore, as odious and insulting as could be imagined for the aspirations and rights that exalted our public spirit at that time."

This fatal coincidence, that the last remaining Spanish government of resistance on the Peninsula had established itself precisely in Cádiz, a city then detested in the Río de la Plata, was blamed for the backwardness and colonial subjugation of centuries. Perhaps, if the Spanish resistance had concentrated in a different locality, the events of May would not have unfolded with the determination they did.

More posts: