From Discourse to Repression: Senator Noroña and His Authoritarian Drift

The senator turns his inauguration into an instrument to suppress criticism and silence opponents

Gerardo Fernández Noroña, an old leftist militant and staunch defender of freedoms when it suited him, has crossed a dangerous line: using his public office to punish, censor, and chastise those who criticize him.

The recent episode he starred in at the Senate of the Republic is not only grotesque but deeply alarming for any democracy. A citizen who dared to confront him was not only exposed in national media but also publicly forced to apologize under the shadow of institutional power, sitting next to the senator himself, as if it were a scene of exemplary humiliation. This was not a mere political response; it was an act of symbolic coercion, sending a clear message: "whoever questions will be punished".

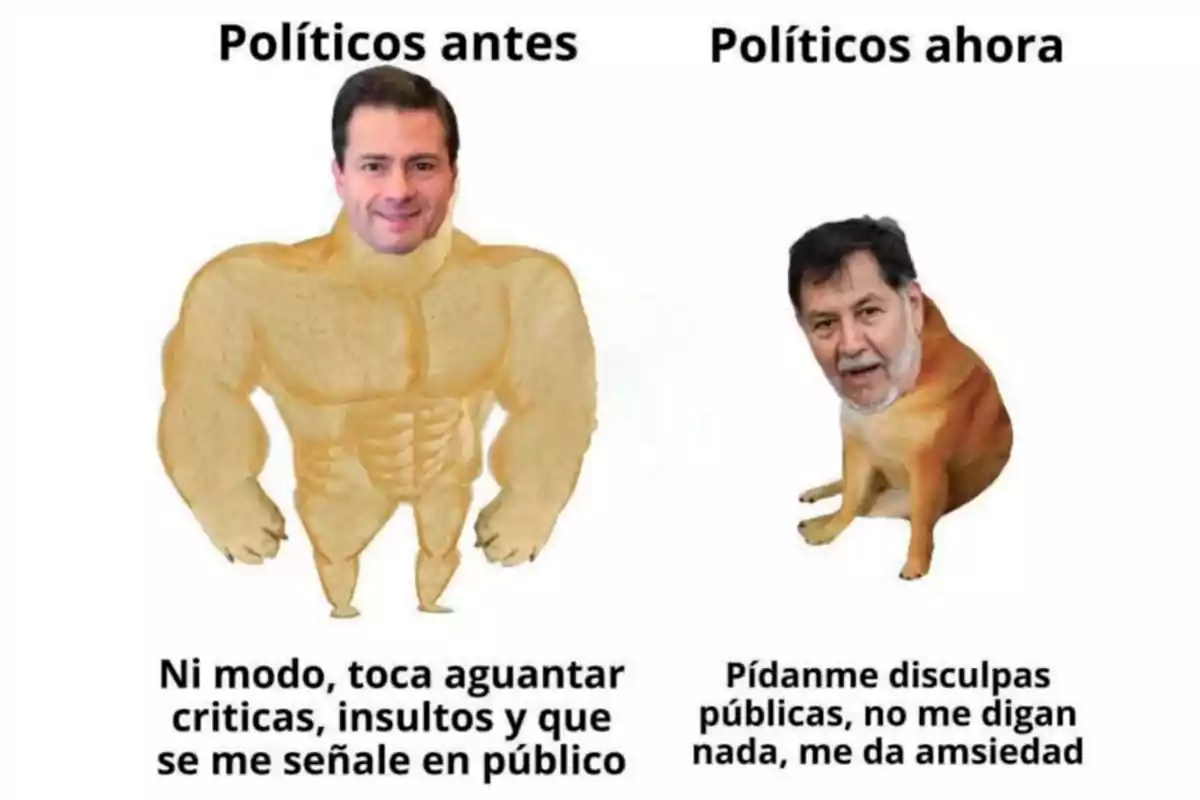

Noroña, who once dressed as a libertarian and revolutionary, has become a small vassal of parliamentary authoritarianism. Unlike presidents like Calderón, Peña Nieto, Sheinbaum, or even AMLO, who have dealt —with more or less grace— with public protests, memes, shouts, or heckling, the senator has decided to use his position to stifle criticism with mechanisms unworthy of a democratic republic.

On the social network X (formerly Twitter), Noroña has blocked accounts like La Derecha Diario and my own, as well as a dozen more citizens, due to the same phenomenon of wounded ego and political insecurity. Instead of debating or simply ignoring, he prefers to silence. But when a public official uses digital platforms to communicate his legislative work and, at the same time, closes access to those who question him, he is violating the principle of freedom of expression and access to information.

Mexican Constitution and international precedents

Article 6 of the Mexican Constitution states that "the expression of ideas shall not be subject to any judicial or administrative inquisition," while Article 7 guarantees that "the freedom to disseminate opinions, information, and ideas through any means is inviolable." These principles are not decorative paper: they are essential guarantees that protect precisely citizens against figures like Noroña, when they feel entitled to intimidate from the seat.

Internationally, cases like this have been condemned. In the United States, courts have ruled that even public officials can't block citizens on social media, as they constitute digital public forums. A clear example was the case of Knight First Amendment Institute v. Trump, where it was established that the then-president violated rights by blocking critical users.

In Spain, the Constitutional Court has affirmed that public figures can't restrict access to official or personal social media if they use them for matters of public interest, as occurred with a mayor who blocked citizens on Twitter.

"Freedom of expression is not a gracious concession of power; it is a cornerstone of democracy."

A silent danger disguised as ideology

When a senator —who in theory should defend it— becomes its executioner, the damage is deep, even if it comes disguised as personal indignation.

This is not a problem of left or right. It is a problem of authoritarianism disguised as ideology. Today it is Noroña. Tomorrow it could be anyone else. If we let this abuse pass, we are allowing public power to become the judge of what can or can't be said in Mexico. And that, quite simply, is unacceptable.

More posts: