The lesson we don't see: national industry and structural poverty

The state and its tentacles keep us in a condition of lethargy and underdevelopment

In days of lesser economic freedom in Uruguay, Argentina, led by the first libertarian president, continues its path toward the total liberation of its population, this time from the burden represented by the so-called national industry.

Structures originating from the old model of Import Substitution Industrialization (ISI), typical of closed economies and promoted as a response to the global crisis of the thirties, have resulted in inefficient and unnatural systems that, far from generating wealth, consolidate structural poverty.

You might also be interested in: The great climate business of the left

As I stated in the article “Uruguayan Mercantilism and Global Protectionism,” this approach remains present in the socialist ideas of our politicians, who promote interventions and corporate privileges.

Ideas like those once enshrined in Article 50 of the Constitution of the Republic: “The State will guide... protecting productive activities whose purpose... replace imported goods...”

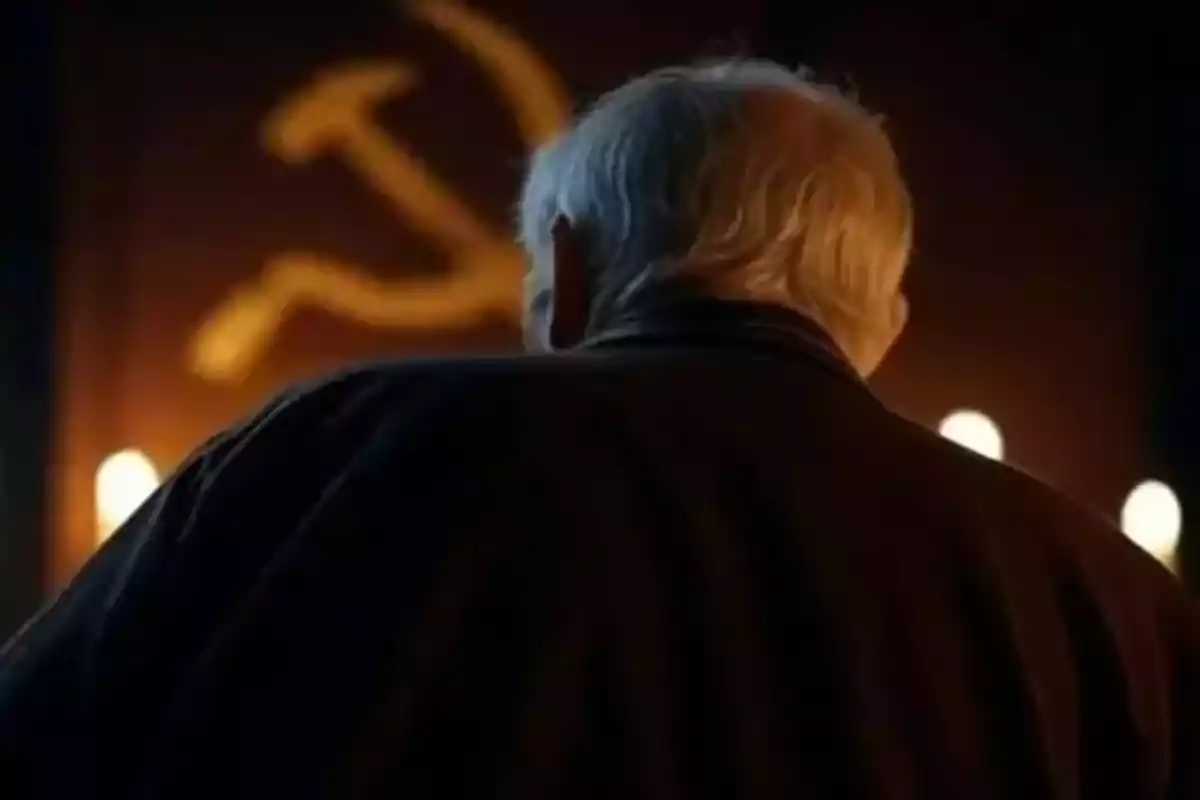

Our “candles” lit to socialism

In Uruguay, previous governments of the Broad Front lit for us the most expensive candles in history, lit to socialism and praised, at another time, by the one who just departed: Funsa, Olmos, Envidrio, Pluna, Alas U, the regasification plant, Antel Arena, among others.

To these examples are added the unpaid debts of Venezuela to Conaprole and the businesses with ANCAP during those same administrations. The most grotesque case is, undoubtedly, that of UPM II, which will impoverish the population until “the third and fourth generation...”

Also read: The Communist Party and its support for the 1973 coup

The heist of the century: a train for UPM

Of the US$ 1000 million initially indicated by the government —which signed the contract for us—, one of the latest estimates (which is always higher) raises the figure to US$ 4868 million.

CPA Ferrere and others estimate that UPM will generate US$ 4173 million in 30 years, between royalties, taxes, and other revenues. But generally, that figure tends to be lower in the end. Once again, ruinous deals for the population.

And that is without considering the losses of well-being and the high costs difficult to quantify caused during the nearly five years it took to build the new railway system.

Forced industry

The Argentine presidential spokesperson announced last week the progressive reduction to zero of import taxes on cell phones, along with other internal levies on their production.

That "national industry," in this case, is an example of how, under state protection, competition is closed off and exclusive privileges are granted that divert resources from the population to sectors with particular economic interests.

When the economy responds to these misallocations by increasing unemployment and poverty, the right thing to do is to free up resources. But here, they insist on continuing to allocate them with privileges. Thus, those who proclaim themselves our “humble servants” only perpetuate poverty.

The salvation of Industry X

Hazlitt, in chapter XIII of his book Economics in One Lesson, explains the fallacy of saving or maintaining unprofitable businesses through privileges granted by the State, under the pretext of preserving jobs that otherwise could not exist.

Fallacy, according to the dictionary, is an argument that seems logical or true, but actually hides a deception. Like this one: that the State can create jobs without negative consequences.

The book is inspired by an 18th-century legacy from the French economist and writer Frédéric Bastiat: the “fallacy of what is not seen.” That is precisely the difference between a good economist, as the Argentine president proves to be, and a bad economist, like those who criticize him without any accuracy.

What is seen today: the 7,000 jobs that some estimate will be lost in the national cell phone assembly industry, or the jobs created with the new UPM plant here.

What many do not see is the increase in the well-being of all those who will no longer be forced to pay overprices, thus having more resources to acquire other goods and satisfy a greater number of needs.

All the new jobs that will be created from the liberation of that money —whether spent or saved— will energize other sectors of the economy.

Related: Macri, Lacalle, and the myth of the political center

In the case of UPM, the jobs that, due to exclusive privileges for a few, will never come to exist are not seen.

Economic theory indicates that, although it will take time for workers to find new employment, what is surprising is the speed with which, in the past, many people have re-entered the labor market.

The lesson exposed more clearly

When the economy is honest, jobs, like other scarce resources —natural, capital, or entrepreneurial effort—, must be available to be used in their best use: where society really needs them.

This doesn't happen when they are artificially allocated by regulations that prevent the harmonious development of the population.

That orientation is only possible if the market signals —the price mechanism— are not distorted by the governmental system.

The fear of unemployment often arises because only part of the process is judged. However, jobs are quickly reassigned to areas where society demands them (not where politicians dictate).

Hazlitt, at the end of the chapter, goes to the heart of the problem: every job created by the State is a job taken from another place where the population needed it, a wrongful reassignment of resources.

Final reflection

I want to be careful because perhaps among the readers there are people or acquaintances who have suffered the loss of a job in a company that stopped producing to start importing. While it is painful, one must consider what is not seen.

Governments often protect companies in sectors with high political interest, while others must struggle with over costs due to a tangle of taxes, regulations, and expensive public services.

Again, only part of the process is judged, but the companies that fulfill the essential role of improving our quality of life —when they can freely pursue their goal of maximizing profits— must be seen in their true dimension.

It is also something that is not always seen: the human dimension of well-understood economics, where companies, if allowed to compete freely, fulfill their role in the harmonious development of society.

More posts: