From the monetary binge to the inflation hangover

How politicians paved the way to the servitude of state money

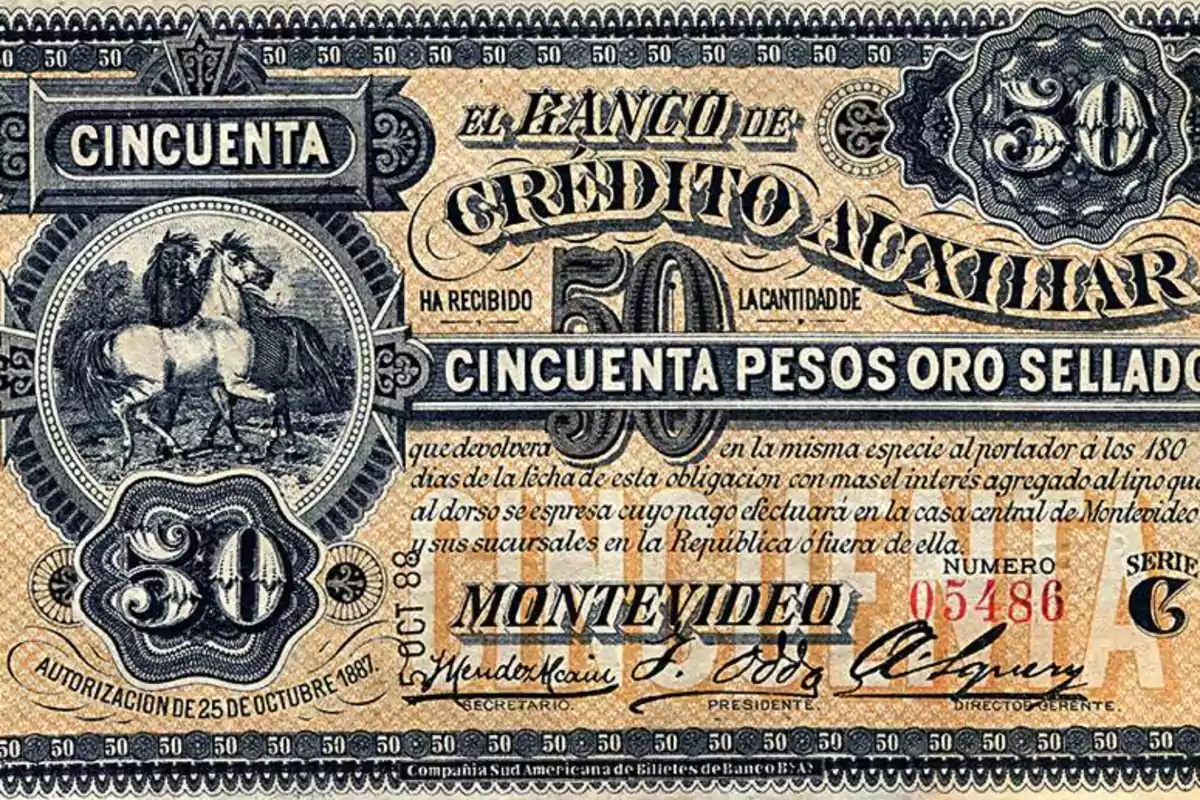

Uruguayan monetary history during the twentieth century could be a typical tale of economic addiction: a rigid gold standard that was actually a corset governments sought to break in order to issue currency without control; a state bank that became the armed wing of political power; and inflation that, disguised as an instrument of the common good, became the cruelest of thieves: the one that robs the poor to fatten the bureaucracy and its clientele.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, Uruguay embraced the gold standard with the enthusiasm of someone discovering a talisman for stability. The idea was simple and seductive: backing the currency with a precious metal to limit issuance and avoid inflation. In theory, it was a commitment to monetary discipline that would curb the state's temptation to print money recklessly.

But the gold standard was not an achievement of its own, but rather a straitjacket imposed from outside, an international corset that the vast majority of Latin American countries had to wear to participate in trade and attract foreign capital. That pursuit was not exclusive to evil imperialists or elites. Leftist intellectuals, such as the socialist Emilio Frugoni, recognized early on that inflation was a kind of regressive tax that struck with particular cruelty at workers, wage earners, and small savers unable to adjust their incomes to the pace of monetary depreciation.

Read more about the Communist Party's financing with irregular money from SUNCA

Here arises the paradox: while inflation was denounced, the state continued to use monetary issuance as its main petty cash, a way to reduce the real value of its debt and finance growing expenses, embodying that old premise that inflation is the most discreet way to rob the people without the people noticing.

It is no coincidence that in 1931, under the pretext of protecting the national economy, exchange controls were established, which meant the official exchange rate was set by Banco de la República. The main objective was to defend the currency, prevent capital flight, and regulate imports. Exchange controls caused a parallel or "black" market due to the artificial fixing of the exchange rate, a system that remained in force until 1974. A prison for private capital that tied the Uruguayan economy to a bureaucratic fate, with rigid controls and an increasingly less free market.

Opinion: the only way out is fiscal liberalization

José Batlle y Ordóñez was the architect of many of the political and social transformations that defined modern Uruguay. The official myth presents him as a humanist reformer, but his almost religious faith in the state was the beginning of the end of economic freedom.

Batlle believed in democracy as a mask for soft authoritarianism. He believed the state should "order" society, protect the weak, and distribute wealth, all from the centralization of power. His monetary policy, based on the issuance of fiat currency and the expansion of public spending, was the prelude to the chronic inflation that Uruguay would suffer in the following decades. The official history, which usually dresses him in the toga of a visionary and statesman, hides the fact that his legacy was also state bureaucracy, centralization of power, and dependence on the public apparatus.

By the mid-twentieth century, the gold standard began to collapse in Uruguay. The pressures of growing public spending, social demands, and international crises made the rigidity of the system unviable. Convertibility gave way to unlimited issuance of unbacked bills, which for the state was like discovering a gold mine: easy money to finance its limitless ambitions. It is no coincidence that inflation coincided with the expansion of public spending and the multiplication of state obligations that no one financed with genuine resources. The systematic devaluation of the Uruguayan peso was the inevitable consequence of an economy subordinated to political power, where the currency lost all real value and the citizenry was trapped in a spiral of impoverishment. With monetary issuance turned into a bottomless petty cash, politicians found the easiest way to finance their projects, clientele, and election campaigns.

The methods of the Uruguayan left to impose its narrative with public money

The cycle is as predictable as it is cruel: inflation punishes the poorest sectors, who can't protect their incomes or savings; capital flight multiplies; economic uncertainty discourages investment; the state responds with more intervention, more spending, and more issuance, feeding the crisis. State interventionism has not been a solution but the problem itself, and the only possible remedy is to restore economic freedom and genuine competition, conditions without which prosperity will remain a mirage.

Mid-twentieth-century Uruguay was built on the myth of the welfare state. In the writings of intellectuals and politicians of the time, this figure was an angel who protected the weak, redistributed wealth, and guaranteed social rights. However, the reality was much less poetic: this welfare state was the great weaver of economic dependence and suffocating bureaucracy. Inflation, far from being an accident or a technical failure, was and is a deliberate tool of the state to finance its excesses and maintain its apparatus. It is no coincidence that periods of greatest monetary issuance coincide with expansions of public spending and growing fiscal deficits. Meanwhile, the economic and political elite always found ways to protect their capital, while the common citizen saw how their incomes were diluted in the inflationary maelstrom.

The enveloped press and the overpricing we all pay

Control over issuance and credit policy translates into a tool to sustain clientele, finance deficits, and expand public spending, but also into the source of uncertainty and insecurity that discourage private investment. Monetary sovereignty without limits or checks is nothing but the freedom to destroy economic value as quickly as bills are printed.

Since the second half of the twentieth century, Uruguay has been trapped in an infernal cycle: recurring crises, chronic inflation, uncontrolled monetary issuance, and state patches that only deepen distortions. Each government, with its particularities, repeated the formula of increasing public spending without controlling issuance. The consequence was episodes of devaluation and capital flight, followed by protectionist measures and price controls that only discouraged production and savings, leaving the country in a situation of stagnation and dependence.

The same Batlle who dreamed of a welfare state ended up creating the foundations of a system that today strangles freedom and economic development. Batllista ideology became a fetish that prevents questioning the disproportionate role of the state in the economy and the need for deep reforms.

Over the past three decades, Uruguayan politicians have shown a curious ability to ignore the lessons of history. Uncontrolled monetary issuance is repeated like a litany: the state's "petty cash" that seems infinite but ends up devouring savings. The batllista mentality—that almost religious faith in the state as the solution for everything—continues to permeate economic policy, with the belief that more intervention is synonymous with greater social justice. However, the reality is that bureaucracy grows, public spending skyrockets, and inflation crushes the most vulnerable sectors.

In 2002, the loss of confidence in the currency, the massive flight of deposits, and the need for international assistance showed the extreme to which a system trapped in the paradox of an omnipresent state and a restricted economy can go. This episode made it clear that without deep structural reforms, Uruguay would remain condemned to periodic crises, growing debt, and social deterioration.

Nonetheless, the substance remains. The 2020 pandemic and its economic consequences brought new pressures to increase public spending and monetary issuance, reinforcing old patterns. Resistance to real change is the expression of a political class that still believes control over the currency is the key to power, regardless of the social cost.

Breaking this vicious circle would require a revolution not only in economic policies, but in mindsets. Real independence of the Central Bank, financial liberalization, and genuine encouragement of savings and private investment are necessary conditions.

But that means shaking off the moth of statism and confronting the bureaucratic leviathan that has colonized the national economy.

The real battle will be cultural and political: convincing Uruguayan society that the common good is not built with controls and punishments, but with real freedoms and respect for property. As long as the chains of irresponsible issuance are not broken, as long as confidence in the currency and financial competition is not restored, history will repeat itself: inflation, crisis, and the broken illusion of prosperity. In that endless spree, Uruguay remains a country that lives in an alcoholic dream of eternal stability, but wakes up every day with the bitter hangover of debt, interventionism, and inflation.

More posts: